No More Dried Up Spinsters – Nancy Jane Moore

There have been a number of different reactions to these essays. Most that I’ve seen have been very positive. But I’ve also spoken with people, generally authors, who felt defensive. At a recent convention, one author told me he felt like it was a language problem, that talking about things like sexism or racism or exclusion meant different things to different people, and to him these had always been conscious forms of abuse and discrimination. Which led to him feeling like he was being scolded for choosing to exclude people.

To his credit, he stepped back and realized that’s not what was being said. So much of what we’re talking about are unconscious attitudes, cultural assumptions we’ve absorbed. I grew up in a middle class, mostly white suburb. As a kid, I saw nothing strange about stories dominated by white people. For years, it never occurred to me that anyone was missing.

For the writers reading this series, the point isn’t to tell you, personally, that you’re Doing It Wrong. The point, at least for me, is to talk about why stories and representation matter. How it affects people. Not to say, “Hey, this is how you must write all your stories, or else you’re a Bad Person,” but to say, “Hey, here’s stuff you might not have thought about before. Think about it…”

With that said, please welcome Nancy Jane Moore.

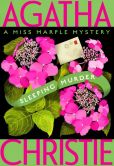

One afternoon, when I wanted to avoid work, I pulled out one of my late mother’s Agatha Christie’s – a book featuring Miss Marple. When I’m procrastinating, I read things that aren’t important to me, but to my surprise, I found myself getting into the book. It wasn’t the plot that drew me in – Christie’s plots were always ridiculous – but the character of Miss Marple.

I loved adventure stories from an early age. Mysteries, spy novels, swashbucklers, anything in which the hero found himself in danger on a regular basis and solved his problems with his fists (or his gun). If they included a whiff of moral dilemma, even better. And since none of the heroes in the available books were ever women, I identified with the male heroes, with Philip Marlow or George Smiley or even – goddess help me – with James Bond.

I wanted to be the hero, not the hero’s girlfriend. I didn’t pretend I was a man – I didn’t want to be a man – but I did pretend that I got to have the adventures. It wasn’t until a co-worker introduced me to C.J. Cherryh’s Morgaine series that I discovered adventure stories about women. That drew me into science fiction, a place I’ve never left, especially when I figured out that if you wrote a story set in the future – or in a fantasy world that never was – you could give a woman agency and adventures without having to explain why she was “exceptional.”

I’ve always been a woman, so craving female heroes in my fiction came naturally to me. But I haven’t always been old. I suspect that when I was younger, I didn’t notice the treatment of old people in fiction. It didn’t occur to me that the dried up elderly spinster wasn’t drawn from real life. But for every “smart as a whip” Miss Marple, fiction has given us thousands of silly old maids, overbearing maiden aunts, and – to give equal time to the married – cheerful grandmothers.

We’ve seen so many of these characters that it takes very little description to convey them. I was reading a story the other day in which an elderly spinster was a very minor character, and I saw her instantly, a stick of a woman, scared of any man, scared of her shadow. I knew what I was supposed to see. These characters have peopled our fiction for so long that we’ve come to believe that they’re real.

And yet, I know a lot of older single women – have known them my entire life, have been one – and not one matches that description. I’ve never met anyone like the typical spinsters of fiction, but I still know what they look like and I know I’m supposed to mock them.

The “click” for me in realizing just how much we stereotype older women was a direct result of my own aging and the aging of my friends, coupled with spending time with people a good deal older than I was while taking care of my father for the last five years of his life. Here’s the most important thing I’ve noticed about all the older people I know: They’re individuals.

I know women who live for their grandchildren. I know those who enjoy their lives, but feel satisfied with what they’ve accomplished. I know ones still pursuing their careers even though they’re well past retirement age, because they love their work. For crying out loud, Hillary Clinton is a grandmother, older than I am, and working very hard to be President of the United States. But I bet no one who ever pitched a novel about the first woman president described her as over 50, much less late 60s.

As for me, I’m in the throes of changing my life. I just moved halfway across the country to live with my sweetheart, embarking on a serious relationship after spending my younger life as a happy spinster. My first novel comes out in August. I still do Aikido, even if I don’t fall down or fly through the air anymore. And I’ve got plans for so many stories I want to write, trips I want to take, experiences I want to have. I am in no way ready to settle into a sedate old age.

I’d like to see more women like me in fiction, and especially in SF/F, where we can bend all the possibilities. Catherine Lundoff has put together a great list of older women characters in SF/F, which she’s updating regularly. But to get a good list, she has defined “older” as women 40 and above. By that standard, the main characters in my forthcoming novel would qualify, though when I wrote them I made them in their 40s and 50s so they would be old enough to have responsible positions as scientists on an interstellar ship. That is to say, middle-aged, not old.

I suspect if you put the cut-off at 50, the list would shrink. And if you set it at 60 or 70, you’d be down to a few crones and witches and, of course, Ursula K. Le Guin’s Odo, who sparked the revolution that gave us the world of The Dispossessed. But Odo’s an outlier. And outside of Odo, I suspect many of the characters are wise crones. Granted that it’s better than the ditsy spinster, it’s still a stereotype.

I want old women who are starship captains and rocket scientists, rulers and generals, adventurers and sages. Let them be grandmothers and happy spinsters on the side from doing what they do in the world, just like the other characters in a story.

And, oh, yes, let them have sex. Old people do, you know. It’s not just something they did in the past. Some old folks are definitely getting it on.

No, I’m not going to tell you how I know that.

Nancy Jane Moore’s science fiction novel, The Weave, will be published by Aqueduct Press in August. Her short fiction has appeared in many anthologies, in magazines ranging from Lady Churchill’s Rosebud Wristlet to the National Law Journal, and in books from PS Publishing and Aqueduct. Moore is a founding member of the authors’ co-op Book View Café. She holds a fourth degree black belt in Aikido and lives in Oakland, California.