The Danger of the False Narrative – LaShawn Wanak

Welcome to the second round of guest posts about representation in SFF.

One of the common refrains in these conversations is, “If you want to see people like you in stories, why don’t you just write them yourself?” There are a number of problems with that statement, one of which author LaShawn Wanak talks about here. How do you create those stories when you’ve grown up being told people like you don’t belong in them?

Stories are powerful. Sometimes we don’t even realize how they’ve shaped our thinking…

Ever since I was a little kid, I’ve known I was a writer. My earliest memories were making up stories about my sisters and cousins. I told of secret tunnels under our neighborhood that took us to crystal-laden caverns. Or our dogs sprouting wings and bearing us off to a land where all animals could talk and fly.

When I was twelve, my grandmother got me a typewriter, and I began to write my stories. By then, I was trying to imitate all the books I read: Robert Silverberg, Anne McCaffrey, Katherine Kurtz, Stephen R. Donaldson, and of course C. S. Lewis. I stopped making up stories of my sisters and cousins, and added my own original characters.

Every single one was white.

It never entered my mind that black people like myself could exist in fantasy novels.

#

Back then, I thought blacks didn’t do epic fantasy. I only saw them confined to dramas dealing with drugs, gangs, prostitution, crime, slavery, segregation, or something dealing with race. If there were black people outside those genres, it was science fiction, like Octavia Butler or Samuel Delany (both of which I did not know about until I entered college). But epic fantasy? No such thing. The closest thing to it would be “magic realism” or stories involving voodoo, because that’s the only way blacks interacted with magic. No elves. No dragons. No swords or sorcery.

Heck, I myself was an anomaly. Growing up on the south side of Chicago, I was picked on by kids around me because I loved to read epic fantasy. Shonnie’s reading the weird books again. Why you reading that junk? It’s just make believe.

I didn’t know any other black kids who loved fantasy as much as I did, so I resigned myself to thinking that I was just that: a weirdo. I never questioned it.

It was a narrative I grew up with most of my life.

#

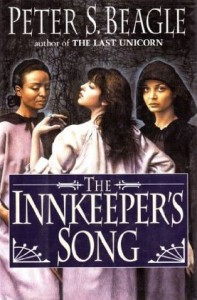

This all changed when I came across Peter S. Beagle’s “The InnKeeper’s Song.” On the cover were three women: a pale woman, a tan woman…and a black woman. With hair. Like mine. I don’t think I even read the book right away. I just stared at the cover for a long time because look there’s a black woman on the cover of a fantasy novel.

This all changed when I came across Peter S. Beagle’s “The InnKeeper’s Song.” On the cover were three women: a pale woman, a tan woman…and a black woman. With hair. Like mine. I don’t think I even read the book right away. I just stared at the cover for a long time because look there’s a black woman on the cover of a fantasy novel.

When I finally I opened the book, I learned her name was Lal. She wasn’t a slave or a hooker. She didn’t have man troubles or drug problems. She was simply searching for her wizard teacher so she could save him, and the world, from destruction.

That book blew my mind. But it didn’t change it.

Not yet.

#

In college, I started writing an epic fantasy novel that had magic, prophesy, political intrigue–and one black female assassin. Although she was a main character, she was seen mostly through the eyes of the main white male character.

Then, I stumbled onto the LiveJournal community, right around the time of RaceFail, and found myself reading NK Jemisen’s essay, “We Worry About it Too“. Here was another black fantasy writer, telling of her struggles of writing people of color in fantasy, and how some things she got right, but others had fallen back on stereotypes that even she didn’t realize was there.

It challenged me enough to look at my unfinished novel and think, what if I told this story from the point of view of the black assassin?

Instantly, I became scared.

Because to write fantasy from a black perspective, I’d have to ignore the narrative that dictated to me for so long that black people don’t read epic fantasy. Black people don’t belong in epic fantasy. They can’t be in fantasy lands riding horses with swords and having adventures. They need to stay in cities and deal with gangs and drugs.

But this is a false narrative.

#

A few weeks ago I had the unfortunate pleasure of hearing a pastor say something problematic about black women. I was hurt and, of course, outraged. Didn’t he think before he said it? How could he say such a thing?

A few days after, I saw someone post on Facebook a tweet from a woman named “Luwanda” who wrote: “Yes u should get vaccines. And so what if that makes your kid artistic. That don’t always mean he’s gay.” Immediately I reposted it, because I thought it was so mind-blowingly ignorant and hilarious.

Then I actually looked up Luwanda’s Twitter feed. She’s a pretty savvy satirist who knew exactly what she was doing when she wrote that tweet. But I only saw the tweet (ghetto language), saw her name (ghetto name) and instantly thought she wasn’t someone to take seriously. It was a knee-jerk reaction—I’ve seen enough news stories, sitcoms, movies that portray the poor black ignorant woman that even though I know it’s a stereotype, there’s still a part of me that thinks it’s true.

And that needs to change.

#

I’m not good at speeches. I don’t like debating people. I’m pretty passive aggressive when it comes to conflict. But I can write stories. Fantasy stories. Epic fantasy stories about black people. Good black people. Bad black people. Magicians. Warriors. Adventurers. People.

The only way to overcome the false narrative is to change it.

Every short story, every novel, every poem, every blog post, can be used to counteract the stereotypes that we as a black people live with daily. And it’s hard, because there are so many naysayers, both from outside and within, who say you can’t do that.

But I know it’s not true, because there’s me, and there are so many other black authors of fantasy. N. K. Jemisen. Nnedi Okorafor. Alaya Dawn Johnson. The more stories people read of us, the more the narrative changes into one that reflects truth:

that we are many, diverse, widespread and utterly,

utterly,

normal.

LaShawn M. Wanak‘s work can be found in Strange Horizons, Ideomancer, and Daily Science Fiction. She is a 2011 graduate of Viable Paradise and lives in Wisconsin with her husband and son. Writing stories keeps her sane. Also, pie.

1. What’s interesting to you about divination?

1. What’s interesting to you about divination? At the same time, though, I do believe in having the gift of foresight, which is very different from seeing the future. When I did research for my story in

At the same time, though, I do believe in having the gift of foresight, which is very different from seeing the future. When I did research for my story in