Not Your Mystical Indian – Jessica McDonald

I remember being a child and getting bags full of plastic Cowboys and Indians–similar to green plastic soldiers, but these came in all colors. The Indians all had bows and arrows and feathered headdresses and buckskins. I never thought much about it, but looking back, my sense was that Cowboys and Indians were something out of history. Almost a mythical thing, from hundreds of years ago.

In Boy Scouts, I was a member of the Order of the Arrow. It was an honor to be voted into this group by my troop, and I remember thinking how cool the Native American lore and ceremonies were. I spent several years as a part of our ceremonies team. Eventually, I remember starting to feel uncomfortable, and asking if we weren’t being disrespectful. I was told that our lodge had worked to research historically accurate regalia, and that we’d worked with local tribes to make sure we were being respectful. At the time, I was satisfied. Looking back, I find it interesting that we never actually spoke to or interacted with anyone with native heritage during our time in OA.

My thanks to Jessica McDonald for sharing her story and perspective here. There’s so much here and in the other guest posts that I wish I’d learned as a kid…

In 1889, the US government opened up Indian Territory for white settlers in an event called the Oklahoma Land Rush. Fifty thousand settlers homesteaded on over two million acres of Unassigned Lands. Unassigned, of course, meant appropriated from Native tribes.

A hundred years after the Land Rush, I was a second grader at Carney Elementary School in central Oklahoma. Carney is the kind of town that small doesn’t begin to describe. We didn’t even have a stoplight to brag about. Farms, baseball, and ubiquitous red soil were about the extent of Carney. For the Land Rush celebration, my school did a re-enactment. White kids played settlers, triumphantly surging over the territory line to claim their homestead—a mark of prosperity and hope.

Native kids played dead Indians, lying prone on the ground.

I stood there, unsure of what to do. You see, I’m mixed race—Cherokee and white. I didn’t know where to go. My teacher asked me which side I’d like to be on.

I told her the settlers.

And as an eight-year-old, why wouldn’t I choose the settlers? They were pioneers, exploring and shaping history. Of course I wanted to be part of the victors. Of course I wanted to be white. I knew my family, but when I looked to the culture around me, the media I consumed, all my heroes were white (and male). That was my reference point for greatness.

I’m way past second grade now, but not much as changed. Sci-fi and fantasy—still my favorite genres—seldom offer more than tropes for Native characters. Let’s take a look at James Cameron’s Avatar. Set on a futuristic death planet where everyone is still inexplicably white, the Na’vi are clearly based on indigenous people and presented as the Noble Savage. They are held up as the ideal, “pure”, and quite literally connected to their planet. And yet, it takes a white dreamwalker to save them, because at the end of the day, they are still savages; they do not possess the sophistication to fight the invaders alone.

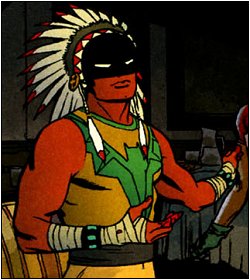

The weird Western novella Sheep’s Clothing by Elizabeth Einspanier utilizes another trope—the Mystical Indian. Half-Indian character Wolf Cowrie is a gunslinger and half-skinwalker that uses his shamanistic powers to fight vampires. The problem with this is that it reduces Native characters to one (false) aspect: their unequivocal badassed-ness, a nature derived from a history filled with war and mysterious magical abilities.

Westerns used the Drunk Indian and Red Devil tropes, but sci-fi and fantasy utilize stereotypes like the Noble Savage and Mystical Indian in a way that’s arguably worse. These tropes, which simultaneously glorify and erase Native identity, are what’s called positive discrimination, and it’s more insidious precisely because, on its face, it appears flattering. “Look at how honorable and incredible these Natives are! We should strive to be more like them.” Even Star Trek fell into this—in the episode “The Paradise Syndrome,” Kirk, Spock, and McCoy encounter an Earth-like planet… with Native people that are not only blends of completely different tribes, but also primitive and uncivilized, despite living in the twenty-third century. Oh, but these Natives are definitely in harmony with nature, and are romanticized for it.

All this does is add to the chasm of otherness; these tropes don’t seek to understand or accurately portray indigenous people, but only use us as one-dimensional morality points or exciting badasses. Sometimes we get to stretch the limits, and we’re hypersexualized instead (Tiger Lily, Pocahontas, any Indian Princess trope).

The proof is in the costuming. Rarely do we see even “positive” portrayals of Natives in anything other than buckskins, beads, and feathers. We are homogenized to the point that the Plains tribes, with headdresses and horsemanship, are the representatives of all indigenous people. Never mind that Algonquin tribes, who lived in lands dominated by forests, had no use for horses. Never mind that the Salish peoples wore outfits woven from cedar and spruce instead of long, feathered accouterments.

A Cree friend of mine encountered a woman in a critique group who had a Shawnee character that was a horse whisperer. When my friend pushed her on why this character was so connected to horses, the (white) woman responded that it was “in his heritage.” Because being Native clearly means you speak horse.

My brother has been asked if he can ride horses without a saddle and if he smokes peyote. During a particularly asinine line of questioning about whether he lived in “modern” accommodations, he shot back, “Yes, because I live in 2014, not 1865.” His tipi has a mortgage, folks.

I’ve read work by otherwise intelligent, compassionate authors who twist revered Native spirits into European-based demons bent on destruction just to fill a plot point and without any regard for the religious traditions behind those spirits.

I don’t speak to animals. I kill plants just by looking at them, and I don’t feel profoundly connected to the earth. I can’t tell the future and I don’t have some sort of sixth sense about otherworldly things. I sure as hell don’t speak in broken English. Relatable Native characters in sci-fi and fantasy are few in far between. Mostly, I see variations on tropey themes. What’s most painful about this in sci-fi and fantasy is that these are genres about the possible. SF/F is supposed to be the genre where the marginalized are heard. We get worlds where magic is real, where we travel to far-away galaxies, where miracles happen. But not where indigenous peoples can escape their stereotype boxes.

And why not? Sci-fi and fantasy are written by people in today’s world, and what we have today is a major football team using a racial slur as their name. We have white University of North Dakota students proudly proclaiming that they are “Siouxper Drunk”; Injun Joe from Tom Sawyer; Disney’s Pocahontas and Peter Pan; NDNs (played by Italian Americans) crying over pollution.

We have NDN heroes that are literally red.

To add insult to injury, even the problematic Native roles in film and TV were largely portrayed by white people. It wasn’t until 1998 with Smoke Signals that we got the first feature-length film by Natives. And yet, in 2013, we still had Johnny Depp playing Tonto and The Lone Ranger winning an Oscar for costuming based on a painting that was itself based on stereotypes. We still have white washing of Tiger Lily.

If you’re thinking, hey, man, it’s just comic books and movies, it’s not like it’s real life—consider the impact this has on young Native and mixed-race kids. Consider why I wanted to be on the white side as a child. I had no reference for modern Natives. I had no role models, no fictional characters to inspire me. All I had were people in revealing buckskins with tomahawks and bows.

Studies show that when Native kids see these harmful stereotypes, their self-esteem suffers, along with their belief in community and their own ability to achieve great things. There’s a danger when you don’t see yourself represented in your culture’s art; there’s an even greater danger when your only representation is fraught with negative messaging and teaches you that you do not belong in this world. You’re a thing of the past, a ghost, a myth.

We’ve got a few reasons to hope the tide is changing. Faith Hunter’s Jane Yellowrock series and Patricia Briggs’s Mercy Thompson series turn the Mystical Indian trope on its head, with nuanced and dynamic Native heroines. Adam Beach, a Saulteaux actor famous for his roles in Smoke Signals, Flags of Our Fathers, and Windtalkers, refuses parts that perpetuate these stereotypes, and his work offers hope for better representation. Lakota rapper Frank Waln creates music that speaks to growing up Native, and advocates for indigenous voices to be heard. Last year, the Senate confirmed Diane Humetewa as the nation’s first Native American woman federal judge.

This year, we even have two sci-fi films that are breaking out of the Native trope mold. Sixth World, written and directed by Navajo woman Nanobah Becker, is based on the Navajo creation story. Legends of the Sky is written and directed by a white man, but is set in the Navajo Nation and features a mostly Native cast.

It’s not nearly enough, but it’s sure as hell better than playing dead on the ground.

Jessica McDonald lives in Denver and is a writer, technophile, gamer, and all-round geek. She serves as the marketing director for SparkFun Electronics in Boulder. She earned her Master’s degree from the University of Denver and holds undergraduate degrees from The Pennsylvania State University, and has worked for everything from political campaigns to game design companies. She has published original research on online user behavior, and writes about marketing, technology, women in STEM, and diversity in media. Her background in the technology and defense industries makes her an insightful critic of gender representation in fiction, film, video games, and comics. Growing up looking white but with Cherokee heritage, she also advocates for representation of people of color and mixed-race characters. Jessica has presented at SXSW Interactive, Shenzhen Maker Faire, American Public Health Association’s national conference, and Pikes Peak Writers Conference. She is the author of the urban fantasy novel BORN TO BE MAGIC and currently is writing a YA novel based on Navajo mythology. Find her on Twitter or on her website.