False Expectations – Matthew Alan Thyer

There’s a lot of SF/F with military elements. You’ve got the space battles of Starship Troopers and Ender’s Game and the Honor Harrington series, the magical wars of Lord of the Rings or Feist’s Riftwar saga, and so much more. But how much does the genre get right? What happens when our stories misrepresent the military experience?

Matthew Alan Thyer talks about the disconnect between the stories he grew up with and the reality of his life in the Army. It’s a somewhat different sort of post than we’ve had so far in this series, but it still comes down to the importance of representation, and the effects when that representation is missing or inaccurate.

It was 1995 and I had just moved from basic training to my first Army technical school. It took the Army several months of bootcamp to disabuse me of pretty much anything my recruiter had shown or said to me, but I clearly recall thinking this was going to be the turning point where they began to programmatically repair those notions and build me up as a person. The point at which I would begin a lifelong pursuit of honor. I’d cross this threshold and “be all I could be.”

Up until my personal introduction to the actual military, the only information I had to go on was the common narrative of military science fiction with a little fantasy thrown in from time to time. Everyone I knew in my parents’ generation had avoided service. My grandfathers were notoriously tightlipped about their time in. My touch point for military life was genre fiction; I loved it and routinely gobbled up that particular narrative of esprit de corps, valor, and duty.

We all know how this story goes. The protagonist signs his name, takes the oath, and learns to trade violence under the watchful yet concerned gaze of a grizzled yet wise mentor. Then, after many tearful good byes, our man goes off to fight the ravaging hordes of giant bugs or merciless otherworldly killers knocking down the gates of civilization. He is the tip of the spear, the edge of the blade, and he is almost always Caucasian, justified and victorious. And that’s what I, in my early adulthood, thought it might be like. I gave my oath believing I was going to fight the “bad guys” — vile torturers, greedy dictators, and ruthless, Cold War Communists — while protecting an idealized America. My recruiters played on my naiveté, showing me compelling, heroic videos of tanks speeding across the desert and guys seated in the military equivalent of gamer nirvana, manipulating drones miles beyond the horizon. I embraced that vision of vigilance and good intent sterilized of consequence. I embraced the only narrative I had to work with.

Little did I know, vets are far more likely to experience divorce, mental illness, domestic violence, addiction, and homelessness than our civilian counterparts. We contemplate and commit suicide much more often than those who did not serve. Let me tell you it can be a challenge to reconcile this statistical reality with the narrative I thought I would be living, and I’ve had to do so on a personal level.

Over the course of the next six years the reason I joined, and did my best, changed. My expectations evolved. Health insurance, a steady pay check, veteran’s preference points — my list got pretty long, but my motivations for doing that job never seemed any better than the people toeing the line on the other side of any conflict. This is not to say that there aren’t bad people out there. I know they’re around. I even served next to a few, and in my experience they tend to be people who feel that the propaganda they cling to is somehow better, more justified, than the pure ideology of the other side. My service taught me that the narrative thread which glorifies duty and service, so popular in the genre fiction I loved to read, is bunk. The people on either side of any conflict are just that. The “bad guys” in North Korea, they just want to eat and have enough left over to visit the dentist.

Knowing full well that it is simply page after page of rubbish, even I’d rather read that Chris Kyle was a super-human hero. The same goes for John Perry, Juan Rico, Captain America or Conan. The best of these stories have power. They can transport us to a place that is infinitely more exciting than the humdrum of our everyday. They may put us amongst comrades in arms whose uncommon loyalty feels somehow closer than that of our own family. Often, as we take on the mantle of the protagonist, we imagine we too will gain super-human ability and rare prodigy.

The problem is that this narrative lacks any bearing to the reality of a martial life, at least as I experienced it. Most kids can’t think that far ahead. I couldn’t. Their bullshit-penetrating radar hasn’t been energized yet. Whether they’re hunkered down, taking cover from indirect fire, or sitting in front of a radio console decoding bad jokes from North Korea, they’re likely living only in the moment — too tired, too lonely, too hungry, and too scared to worry overly much about why they are there. I did the job before me because it’s what I said I would do.

Then one day they leave all that behind and they re-enter a world that already seems convinced of their heroism and valor. They rejoin a society that has set the bar of expectation at the level of its fiction. This is when things get worse.

As a rule I don’t particularly like to talk about the details of my service. With the exception of a few amusing anecdotes that can be shoe horned into the popular narrative, my time-in was mostly a lot of lonely, bored, and tired, punctuated by brief yet profound moments of terror and/or horror. Needless to say, now I know why my grandfathers were both so tight lipped about their service. Hopefully I deal with those moments, all of them, just a little bit better.

I will say that getting the job done almost never requires the heroics we find in genre fiction. I was trained as a cryptanalyst, spent more than a little time working on diesels in the motor pool, and never once drove a 60 ton tank at flank speed into battle shouting my defiance as I independently broke an advancing line of H.I.S.S tanks. So put on your empathy pants and imagine how I feel each and every time someone asks me “what did you do?” I can see the anticipation on your faces, you’re waiting for a tale that will rival Ender’s. I sort through my mental rolodex of memories and know there’s nothing in there that will fulfill the elevated expectations most people have of vets. It sure feels a lot like being told your service has been judged and found wanting. Not a “hero?” You may be worthless.

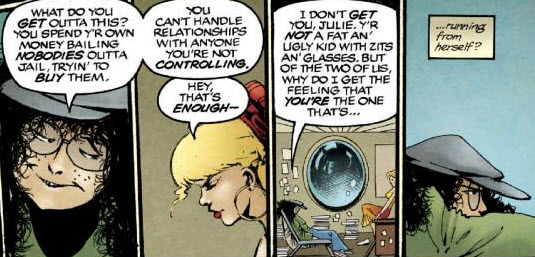

If the stories we tell ourselves shape our understanding of reality, then the popular myth of military heroism has formed our collective expectations of what constitutes a hero. This person cannot be a Puerto Rican woman who was drafted in World War II to save GIs riddled with shrapnel any more than it can defy the archetype of the stoic brute who fights for God and country. But imagine, what if Hercules were experimenting with Buddhism. Perhaps he is deeply conflicted about the things he is duty bound to do. Maybe he feels as if he has taken a nose dive into a rat hole.

That rat hole is the irreconcilable difference between reality and the popular myth. The void between a false expectation and experience is a reductive purgatory with a dark gravity at its center.

A life dedicated to the swift and efficient exchange of violence, regardless of whether it ever sees combat, is a changed life. It is a life keenly aware of immediate consequence. It assumes it is not in possession of full agency, it seeks authority, and more often than not, it lacks foresight. The internet is littered with accounts of veterans attempting to decompress, to adjust to the demands of a civilian lifestyle. So are the undersides of bridges and busy street corners where homeless vets tend to congregate. Unfortunately even Captain Whitedude McManlypecs is vulnerable to all of this.

As an author I am uninterested in feeding a lie, even a popular one. These days my intention is to be the best writer I can be, and this makes it difficult for me to knowingly cut consequence from my tales. Sure I want to transport my readers, entertain them as much as I can, but I believe I can still bring them into a story without relying on worn out tropes that just aren’t true. As a vet I see this sort of thing as an unintended contribution to the very same propaganda that suckered me in the first place, and it irks me because it is dishonest. As a person, I am war weary. The martial solution seldom solves anything and where I find it in our stories it seems, at best, lazy.

“Why is it important I see my veterans clearly?” you may ask yourself. “Why can’t you just let me enjoy my stories?” The stories we tell ourselves have a shape to them, in turn those stories shape us. I think we lose sight of the fact that the key word in the phrase “military fiction” happens to be fiction. These stories grant a tacit sort of permission to ignore anything unpleasant. When we see vets struggling we tend to assume that they have it coming, that their current situation is of their own making. We assume that they are broken and cannot be fixed and consequently treat them with callous disregard. We forget that there is a price to war.

Matthew Alan Thyer writes science-fiction and speculative cli-fi. Prior to finding his voice as a writer he worked as a signals analyst, operations engineer, wildland firefighter, backcountry ranger, kayak guide, and river rat. His hobbies include trail running, backpacking, kayaking, and paragliding. You can enjoy his first book The Big Red Buckle.

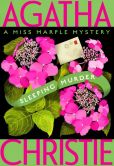

When I read Christie as a kid, I didn’t much like the Marple books, yet all these years later, I found myself captivated by this smart “elderly spinster.” Odd. Then I realized what had happened: I got old. Maybe not as old as Miss Marple, who is probably somewhere between 60 and 80, depending on the book, but definitely not young, not cute, not the object of men’s desire. All of a sudden, the idea that the main actor in a story could be the older woman appealed to me.

When I read Christie as a kid, I didn’t much like the Marple books, yet all these years later, I found myself captivated by this smart “elderly spinster.” Odd. Then I realized what had happened: I got old. Maybe not as old as Miss Marple, who is probably somewhere between 60 and 80, depending on the book, but definitely not young, not cute, not the object of men’s desire. All of a sudden, the idea that the main actor in a story could be the older woman appealed to me.

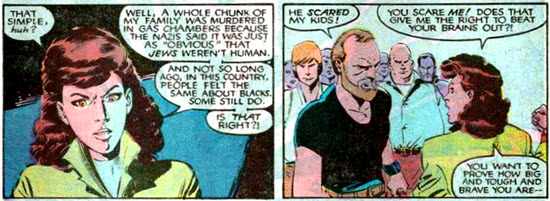

Next, I found Marge Piercy’s He, She, and It. Piercy brings the golem legend into science fiction by playing on its parallel to the android, with plenty of Jewish culture and history to provide setting, context, and flavor. Some of it was the result of extensive historical research, but some of it was the kind of flavor that only experience can provide. Someone else in the world knew what it was like to grow up with a grandmother like mine, with holidays I celebrated. I’d been the only Jewish kid in my class—for five years, the only one in my whole school—so I’d never had a friend who grew up with the same rituals and references I did. To find it in a book was to find a friend.

Next, I found Marge Piercy’s He, She, and It. Piercy brings the golem legend into science fiction by playing on its parallel to the android, with plenty of Jewish culture and history to provide setting, context, and flavor. Some of it was the result of extensive historical research, but some of it was the kind of flavor that only experience can provide. Someone else in the world knew what it was like to grow up with a grandmother like mine, with holidays I celebrated. I’d been the only Jewish kid in my class—for five years, the only one in my whole school—so I’d never had a friend who grew up with the same rituals and references I did. To find it in a book was to find a friend.

When I started the brainstorming process for what would eventually become my debut novel, I initially assumed I’d write my mathematically-superpowered lead character as a man. Probably a white man. Because … well, because. Something-something-mumble-blah about me being a nonwhite woman, and if I wrote my first lead as a nonwhite woman, no matter how different she was from me, wouldn’t that feel too contrived?

When I started the brainstorming process for what would eventually become my debut novel, I initially assumed I’d write my mathematically-superpowered lead character as a man. Probably a white man. Because … well, because. Something-something-mumble-blah about me being a nonwhite woman, and if I wrote my first lead as a nonwhite woman, no matter how different she was from me, wouldn’t that feel too contrived?

Child-me saw an assault survivor who still got to be a badass. Leia left Tatooine and returned to her life as a leader of the rebellion. No one treated her differently or told her she couldn’t do the things the boys do because someone might rape her. At the end of the movie, she got the dashing rogue and the happy ending.

Child-me saw an assault survivor who still got to be a badass. Leia left Tatooine and returned to her life as a leader of the rebellion. No one treated her differently or told her she couldn’t do the things the boys do because someone might rape her. At the end of the movie, she got the dashing rogue and the happy ending.