In February of 2010, I began collecting information from professionally published novelists. My goal was to learn how writers broke in and made that first big novel deal, and to use actual data to confirm or bust some of the myths about making it as a novelist.

My thanks to everyone who participated, as well as the folks at Smart Bitches Trashy Books, Book View Cafe, SFWA, SF Novelists, Absolute Write, and everyone else who helped to spread the word.

The survey closed on March 15, 2010 with 247 responses. For those interested in the raw info, I’ve posted an Excel spreadsheet of the data with all identifying information removed. You can download that spreadsheet here.

I’ve broken my write-up into nine parts:

- The Data

- Short Story Path to Publication

- Self-Publishing Your Breakout Novel

- The Overnight Success

- You Have to Know Somebody

- Can You Boost Your Odds?

- Survey Flaws

- Other Resources

- Final Thoughts

The Data

For this study, I was looking for authors who had published at least one professional novel, where “professional” was defined as earning an advance of $2000 or more. This is an arbitrary amount based on SFWA’s criteria for professional publishers. No judgment is implied toward authors who self-publish or work with smaller presses, but for this study, I wanted data on breaking in with the larger publishers.

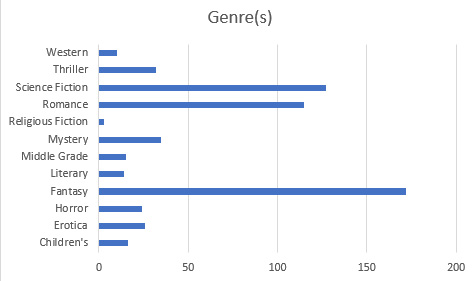

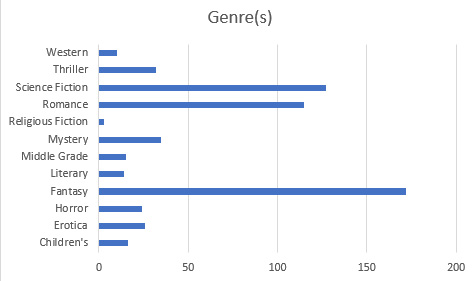

247 authors from a range of genres responded. One was eliminated because the book didn’t fit the criteria (it was a nonfiction title). A random audit found no other problems. The results were heavily weighted toward SF/F, which is no surprise, given that it was a fantasy author doing the study. But I think this is a respectable range:

The year in which authors made their first sale covered more than 30 years, from 1974 to 2010. The data is heavily weighted toward the past decade.

There’s the background information in a nutshell. With that out of the way, let’s get to the first myth.

The Short Story Path to Publication

Back when I was a struggling young author in the late 90s, I received a great deal of contradictory advice about how to break in. Many writers told me I had to sell short stories first to hone my craft and build a reputation so agents and editors would pay attention to me. Others said this was outdated, and these days I could skip short fiction if I wanted and just jump straight into novel writing.

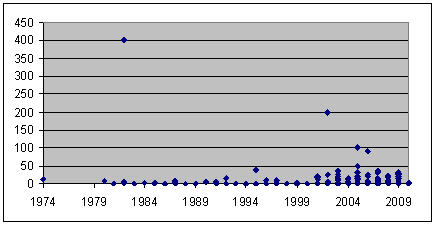

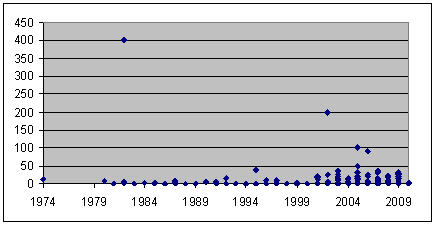

So do you really have to sell short fiction first? I asked how many short stories people sold, if any, before making that first professional novel sale. Answers ranged from 0 to 400 short fiction sales. On average, authors sold 7.7 short stories before selling the novel.

Next I looked at the median, the midway point in the sample. The median number of short fiction sales was 1, meaning half of the authors sold more than this many, and half sold fewer.

But let’s make this even simpler. Of 246 authors, 116 sold their first novel with zero short fiction sales.

Possible Data Quality Issue: The question was “How many short fiction sales, if any, did you have before making your first professional novel sale?” Several authors noted that they only included “professional” short fiction sales, which might reduce the numbers. But even so, the idea that you must do short fiction first appears busted. Not only that, but looking at a scatterplot of the number of short fiction sales and the year of the first novel sale, this appears to be busted going back at least 30 years.

I believe short fiction sales can help an author. One author noted that they were contacted directly by an editor who had read the author’s short fiction and wanted to know if the author had a novel. Personally, I found that short fiction helped me a lot with certain aspects of the craft. And of course, a lot of us just enjoy writing short stories. But it’s not a requirement to selling a novel.

Self-Publishing Your Breakout Novel

For as long as I’ve been writing, some authors have been announcing the death of traditional publishing. Especially with the growth of print-on-demand and electronic publishing, I hear that self-publishing is the way to go. The idea is that if you self-publish successfully, you’ll attract the notice of the big publishers and end up with a major contract, like Christopher Paolini did with Eragon.

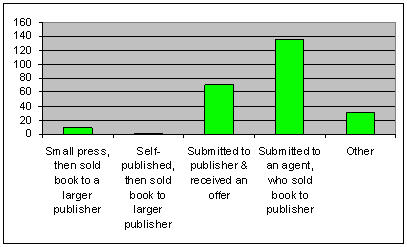

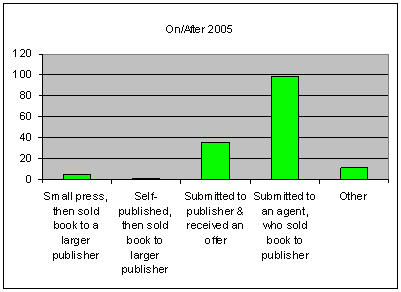

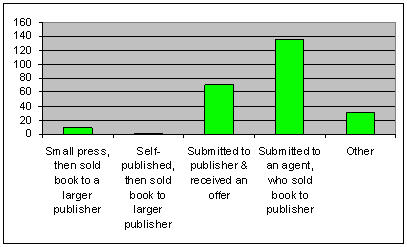

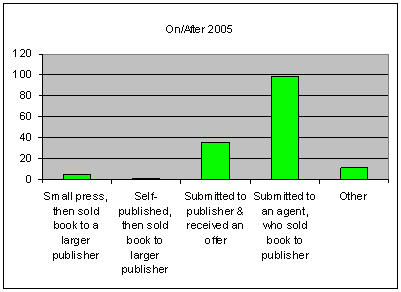

One of the survey questions asked how authors sold their first novel to a professional publisher. The options were:

- Self-published, then sold the book to a professional publisher

- Published with a small press, then sold the book to a professional publisher

- Submitted directly to a professional publisher, who bought it

- Submitted to an agent, who sold the book to a professional publisher

- Other

To those proclaiming queries and the slush pile are for suckers, and self-publishing is the way to land a major novel deal, I have bad news: only 1 author out of 246 self-published their book and went on to sell that book to a professional publisher. There was also 1 “Other” response where the author published the book on his web site and received an offer from a professional publisher. (It should be noted that this author already had a very popular web site, which contributed to the book being noticed and picked up.)

Just to be safe, I ran a second analysis, restricting the results to only those books that sold within the past five years. PoD is a relatively new technology, so it’s possible the trends have changed. But the results are pretty much identical.

This does not mean self-publishing can never succeed, or is never a viable option. (I.e., please don’t use this as an excuse for a “Jim hates self-publishing” rant.) However, for those hoping to leverage self-published book sales into a commercially published breakout book (a la Eragon), the numbers just aren’t in your favor. For the moment at least, the traditional pathways — submitting to an agent, submitting directly to the publisher — still appear to be the way to go.

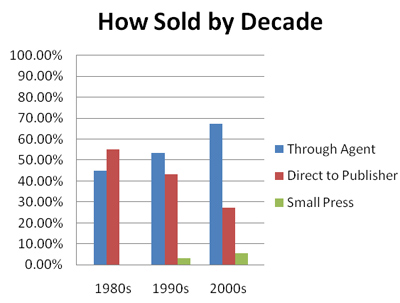

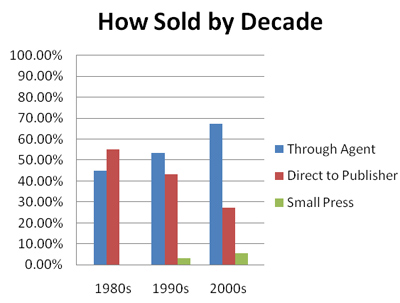

Also, please see below for Steven Saus’ graph showing the trend away from submitting directly to the publisher and more toward querying agents in recent years.

The Overnight Success Story

When I started writing, I figured it was easy. I thought anyone could do it. Having zipped off my first story, I assumed fame and fortune would soon be mine. And why not? How often do we see the movies where someone sits down at the computer, and after a quick writing montage, voila! They’re a published author. (Generally this seems to mean big book tours, winning awards, hanging with Oprah, and living the good life.)

So how long does it take to sell that book? Of our 246 authors, the average age at the time they sold their first professional novel was 36.2 years old. The median was also 36, and the mode was 37. Basically, the mid-to-late 30’s is a good age to sell a book.

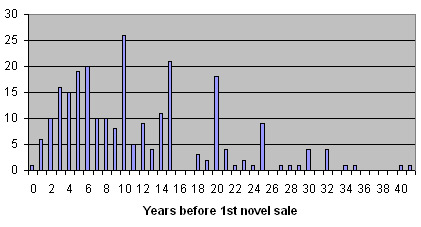

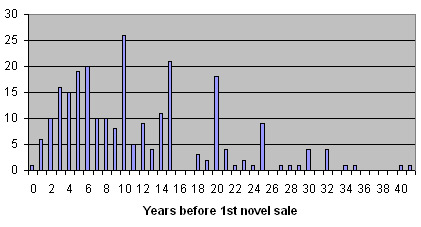

But that doesn’t tell us how long these authors were working at their craft. So the very next question in the survey asked, “How many years had you been writing before you made your first professional novel sale?”

The responses ranged from a single respondent who said 0 years, all the way to 41 years, with an average of 11.6 years. Both the median and the mode came in at an even ten years.

You could argue that the single response from someone who had been writing for 0 years proves that overnight success can happen, and you’re right. It can happen. So can getting struck by lightning.

Here’s the breakdown in nice, graphical form:

I also asked how many books people had written before they sold one to a major publisher. The average was between three and four. Median was two. I was surprised, however, to see that the mode was zero. 58 authors sold the first novel they wrote. Still a minority, but a larger minority than I expected.

I’m still going to call this one busted. Not as thoroughly busted as I would have guessed, but the bottom line is that it takes time and practice to master any skill, including writing.

You Have to Know Somebody

This one goes back to the idea that it’s nigh impossible to break in as an unknown writer. You have to have an in. Without those connections, editors and agents will never pay you the slightest bit of attention.

This was a little trickier to test. I asked two questions:

1. What connections did you have, if any, that helped you find your publisher?

- Met editor in person at a convention or other business-related event

- Knew them personally (not business-related)

- Introduced/referred by a mutual friend

- Other

2. What connections did you have, if any, that helped you find your agent?

- Met editor in person at a convention or other business-related event

- Knew them personally (not business-related)

- Introduced/referred by a mutual friend

- I sold my book without an agent

- Other

The most popular response in the “Other” category was “None” or “No connection at all.” Ignoring the “Other” category for the moment, all other responses were selected a grand total of 162 times. More importantly, 185 authors listed no connections whatsoever to their publisher before selling their books. 115 listed no connections at all to any agents, either. (62 others added that they did not use an agent to sell their first book.)

Combining the agent and publisher questions, a total of 140 — more than half — made that first professional novel sale with no connections to either the publisher or the agent.

Here’s the percentage breakdown:

Met editor at a convention: 17%

Knew editor personally: 3%

Referred to editor: 11%

Met agent at a convention: 11%

Knew agent personally: 4%

Referred to agent: 21%

Did not use an agent: 25%

The “Other” categories also included a small number of authors who reported winning contests, short story sales that attracted interest, industry connections, and in one case, SFWA membership.

My conclusion is that connections can certainly help. Agent referrals in particular — it’s always nice to check with other authors to see who represents them, and if you can get a referral, so much the better. But the idea that you have to have a connection? Or even that most authors knew someone before they broke in? Busted.

Can You Boost Your Odds?

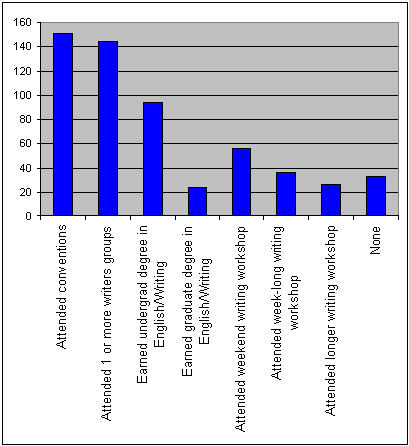

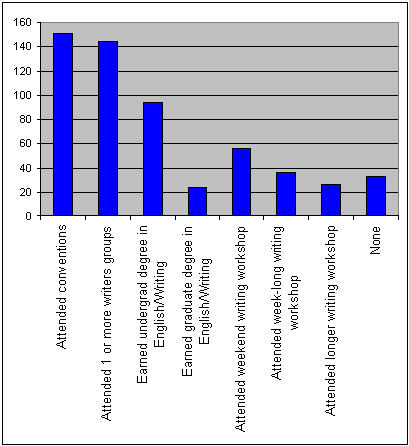

As has been pointed out (by my own agent, among others), while connections aren’t required, they can be helpful. I wanted to know what other steps authors took to try to improve their chances, and asked whether participants had done any of the following:

As has been pointed out (by my own agent, among others), while connections aren’t required, they can be helpful. I wanted to know what other steps authors took to try to improve their chances, and asked whether participants had done any of the following:

- Attended conventions

- Attended one or more writers groups

- Earned an undergrad degree in English/Writing

- Earned a graduate degree in English/Writing

- Attended a weekend writing workshop

- Attended a week-long writing workshop

- Attended a longer writing workshop

- None of the above

By far, the two most popular choices were conventions and writers groups, both of which were reported by more than half of our novelists. The least popular choice? The graduate degree in English/Writing. (As someone who holds an MA in English, I’m trying not to be depressed about that one.)

The full breakdown looks like so:

Remember, this is correlative data, not causative. However, I decided to take a look at a few more correlations, taking the writers from each of these categories and examining how many years it took to make that first pro novel sale. I bolded the highs and lows.

Full Group: Average 11.6 years, median 10, mode 10

Conventions: Average 10.5 years, median and mode unchanged

Writers Groups: Average 10.5 years, and median drops to 9.5

Undergrad Degree: Average 9.8 years, median 6.5, mode 3.5

Graduate Degree: Average 11.8 years, median 10, mode 6

Weekend Workshop: Average 10.7, median 8.5, mode 3

Week-long Workshop: Average 10.7, median 8.5, mode 6

Longer Workshop: Average 11.6, median 10, mode 6

None: Average 15.7 years, median 15, mode 9

I’m reluctant to draw too many conclusions from this, or to say that any one category will definitely help you break in. But looking at the “None” category, I think it’s safe to say that writers who are more actively trying to get out and build their careers — in any one of a number of ways — tend to break in faster than those who aren’t.

Survey Flaws

This was not a perfect study. It wasn’t meant to be. I wanted a large enough sample to start to see some trends, but I’m not qualified to run a full-scale, controlled study. Nor do I have the time. In the interest of full disclosure, here are the flaws I’m aware of.

1. Sample bias. I’m a fantasy author. When I announced the survey and asked for authors to participate, I knew the results would be heavily skewed toward SF/F writers in my network. I did some outreach to spread the word to other writing groups and blogs, but the results are still weighted toward SF/F and may not apply as strongly to other genres.

2. Question imprecision. Several questions were imprecisely worded. For example, one question asked “How many times, if any, was your novel rejected before it sold to a professional publisher?” I received enough comments and questions about this, asking whether I meant publisher rejections, agent rejections, or both, that I did not include the final data in my write-up. I’m also unhappy with one of the networking questions which asked if you were introduced/referred to your agent or editor. “Referral” is fairly broad, and could mean everything from a personal letter of recommendation to an author saying “Oh yes, Bob’s my agent and I think he’s open to queries right now.”

3. Can’t prove cause/effect. This is a weakness of correlative data. I think the data worked well for busting certain myths, but if I catch anyone saying things like “Jim Hines proved that if you get an undergrad degree in English, you’ll sell a novel faster,” then I will personally boot you in the head. See here for a good example of correlation =/= causation re: pirates and global warming.

4. Limited scope. I restricted this survey to authors who had published at least one novel with a professional ($2000 or higher advance) publisher. Not everyone shares the goal of publishing professionally. For those who prefer the small press, non-fiction, script writing, short fiction, or other forms of writing, the path to breaking in might be very different.

I’m sure there are other flaws. However, it was my goal and my hope that even with these problems, the data I gathered would be useful in talking about how writers break in, and would be much better than the anecdotal “evidence” usually cited in such conversations.

Other Resources

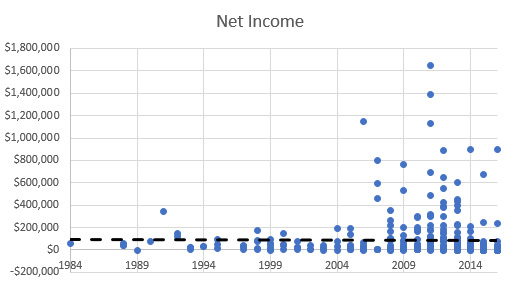

Steven Saus’ Analysis of my Survey Data: Steven ran my numbers through some heavy-duty statistical software and came up with all sorts of info, including this graph showing the apparent trend in how submissions have moved from direct-to-publisher more toward querying agents over the past few decades. For those who like to geek out on numbers and statistics, I recommend checking it out.

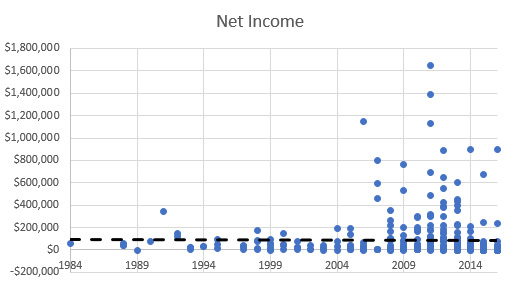

Tobias Buckell’s Author Advance Survey: Data from 108 authors about novel advances, showing trends over time and over the course of authors’ careers.

Megan Crewe’s Publishing Connections Survey: Data from 270 authors on whether you need connections to break in. Her results tend to match my own on this one.

SFWA’s Online Information Center: Includes essays, resources, and advice for new writers from the Science Fiction & Fantasy Writers of America. (Thanks to Charlie Stross for the link.)

Final Thoughts

My thanks once again to everyone who participated in the study, who spread the links to other writers, and for all of the support and encouragement. I’m quite pleased with the way this turned out, and I hope it’s helpful to others.

In conclusion (and in true Mythbusters style) I present you with this artistic rendering of my editor when she learns how much time I’ve spent on this survey instead of working on my next book:

As has been pointed out (

As has been pointed out (