The Nebula and Hugo awards are generally considered to be two of the most prestigious and well-known awards for science fiction and fantasy literature. As a result, lots of authors would really like to win them.

I won a Hugo in 2012 for my fan writing about SF/F, and I was on the Nebula preliminary ballot once — back when the Nebula awards had a preliminary and a final ballot. I have brilliant writer (and editor) friends who have shelves full of Hugos and/or Nebulas. I have equally brilliant writer/editor friends who’ve never even been nominated.

I won a Hugo in 2012 for my fan writing about SF/F, and I was on the Nebula preliminary ballot once — back when the Nebula awards had a preliminary and a final ballot. I have brilliant writer (and editor) friends who have shelves full of Hugos and/or Nebulas. I have equally brilliant writer/editor friends who’ve never even been nominated.

So how does an author go about getting on the ballot? There isn’t one Right Answer to that question, but I’d suggest the first step would be to understand how the awards work. Authors do not submit their work for consideration for either the Hugo or the Nebula. Instead, works are nominated and voted upon by members of the Science Fiction/Fantasy Writers of America (SFWA) in the case of the Nebula, and members of the World Science Fiction Convention (Worldcon) for the Hugos.

In theory, members nominate what they believe are the best works in each category. From those nominations is born a final ballot. Members vote for the best, and a handful of writers get to figure out how to transport a hefty trophy home. (Taking a Hugo — shaped like a rocket — through airport security can be an adventure…)

All right, if authors can’t submit their work for consideration, what can they do?

Do Nothing.

This is certainly the easiest approach, in many ways. Just write your best work, and trust readers to find it and nominate it for consideration. In an ideal world, this would result in the best stuff being nominated and winning each year.

This is not an ideal world. Some works receive much more publicity and promotion than others. A brilliant book by an unknown author might be seen by far fewer people than a mediocre book by a bestselling author. A story in a popular magazine or anthology will receive more attention than a story in a smaller or more niche market.

Some would argue that doing nothing is the professional and classy approach to awards. I can understand where they’re coming from, and if all else was equal, I’d probably advocate the same thing. But as we’ve seen again and again, all things are not equal…

Post a Roundup of Your Eligible Works

As awards season approaches, more and more authors are posting a list of their award-eligible work from the previous year. Here’s mine from 2017, as one example. This works in two ways.

As awards season approaches, more and more authors are posting a list of their award-eligible work from the previous year. Here’s mine from 2017, as one example. This works in two ways.

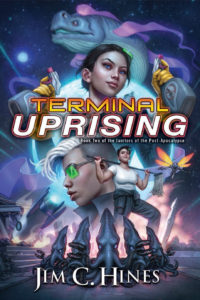

- It reminds your readers about stuff they may have read but forgotten about. I had a new book out a few weeks ago, but by the time awards season rolls around next year, people might not remember the continuing adventures of Jim’s space janitors. A roundup post can jog folks’ memories.

- It lets people know about work they might have missed. I self-published a Magic ex Libris sequel last January, but because it wasn’t through my big publisher, fewer people heard about the story. Someone who’s a fan of your work might discover something that slipped past them, and decide to check it out and see if it’s nom-worthy.

There will be people who say eligibility lists are tacky and unprofessional. I’m not one of those people (obviously). I see nothing wrong with reminding people what you’ve had published. As a writer and often-nominator, I appreciate the reminders and the chance to check out things I missed.

Amal el-Mohtar has a good post from 2014 on this topic: Of Awards Eligibility Lists and Unbearable Smugness.

Share Copies of Your Eligible Works

Unsolicited: When I first joined SFWA, I’d get a handful of books in the mail each year from authors asking me to consider nominating their books for the Nebula. These days, I’ll get the occasional email linking to a story or offering to send me an e-book for consideration.

I don’t know that I’ve ever nominated something based on this kind of cold-call from a stranger. And in 2019, it gets really easy to cross the line into spam. At least when people were sending me books, they had to look up my individual address in the SFWA directory and pack up the book with a cover letter and pay postage to get it to me.

Nowadays, an email to “Dear Reader” with my email address in the BCC: field is likely to go straight to the junk mail folder.

Posted Online: Making your work available online, or linking to where it’s been published online, is a less intrusive and obnoxious way of sharing your stuff. This goes well with the eligibility list approach I mentioned before.

My contracts often prevent me from posting things online. As an alternative, I usually note in my eligibility post that I’m happy to email a copy of an eligible story to anyone who’s interested and will be nominating. But I’m not comfortable with sending things out unsolicited.

(The corollary here is that if you’re going to be nominating, it doesn’t hurt to contact an author or publisher if there’s something you’re particularly interested in reading and considering for the award. I mean, the worst they can say is no, right?)

Logrolling/Vote-Swapping

“Psst. Hey, buddy — I’ll nominate your book for the Nebula if you nominate mine!”

It happens. I don’t think it happens as much as it used to, though I don’t have hard data one way or the other.

It’s also, in my opinion, pretty dickish. This approach may get you some extra nominations. It will also quickly get you a reputation as That Author, the one who doesn’t give a damn about whether or not a book is any good, and just wants to cheat their way onto the ballot.

Technically, it may not be cheating — but while this approach might not violate the letter of the rules, it’s pretty blatantly cheating the spirit of the thing. And it’s unlikely to win you an award.

Slates

::Dons helmet and flame-resistant suit::

In simplest terms, I think of slates as attempts to organize a group to vote for the same (or similar) handful of works in an effort to get them onto the ballot. (Often, but not necessarily, for reasons other than the strength and quality of the slated work.)

There are a ton of eligible works every year, and people’s tastes can vary widely. Also, not everyone who’s eligible to nominate does so. For these reasons, a relatively small group of people voting in lockstep can have a disproportionate impact on what makes it onto the final ballot.

We saw this for several years with the Hugo Awards, beginning with Larry Correia’s “Sad Puppy” slate in 2014. Those were some ugly, painful, frustrating years. Slates had varying levels of effectiveness at getting works onto the ballot, but slate-nominated works pretty much universally lost — often coming in behind “No Award” in their categories.

Some authors were very deliberately and strategically trying to game the system to get their own work and/or the work of their friends onto the ballots. Other authors were unaware they’d been added to a slate, and were dragged into the resulting mess against their will.

The issue of slates has come up again this year, reopening old wounds for some of the folks who got caught up in the Hugo slate issues a few years back.

What’s the difference between a Slate and a Recommended Reading List? If someone posts a list of who they’re nominating, is that a Slate?

None of these criteria are absolute, but here are some of the things I look at.

- Are people being encouraged, explicitly or implicitly, to vote for the same specific set of works?

- Is the list mostly or entirely made up of works by members of the same group being pushed to use that list for nominating/voting?

- How much of the focus is on Proving a Point?

- Is the creator of the list genuinely, visibly enthusiastic about the works?

Like the logrolling/vote-swapping approach, slates can get things onto a ballot, but they also tend to hurt a lot of people, including the nominated authors (as everyone’s left wondering if their work would have made the ballot on its own merits), and those authors pushed off the ballot by this kind of bloc-voting approach.

Buy Lots of Voting Memberships

This wouldn’t work for the Nebulas, but for the Hugo Award, if you bought enough memberships, you could essentially nominate and vote multiple times. It’s been alleged that this tactic was used in 1987 to get Black Genesis by L. Ron Hubbard onto the ballot.

The book did indeed make it onto the final Hugo ballot. It lost, coming in last place, below “No Award.”

In other words, if this was a vote-buying scheme, it was a very expensive way to lose an award (badly) and tarnish the reputations of those involved.

#

Inclusion of various tactics listed above is not endorsement (duh). And none of these approaches guarantee your work will ever be nominated. That’s not how this works. Awards are nice, but they don’t define success or failure in the field.

Keep in mind that awards have different expectations and histories and cultures. The rules and expectations for the Hugo or Nebula Awards might be very different from other awards.

Ultimately, my best advice would be:

- Write the best stuff you can.

- Never assume you’re entitled to an award.

- Don’t be a dick.

This got really long. I’m sure I’ve still missed some things. Thanks for reading, and feel free to discuss further in the comments.

I won a Hugo in 2012 for my fan writing about SF/F, and I was on the Nebula preliminary ballot once — back when the Nebula awards had a preliminary and a final ballot. I have brilliant writer (and editor) friends who have shelves full of Hugos and/or Nebulas. I have equally brilliant writer/editor friends who’ve never even been nominated.

I won a Hugo in 2012 for my fan writing about SF/F, and I was on the Nebula preliminary ballot once — back when the Nebula awards had a preliminary and a final ballot. I have brilliant writer (and editor) friends who have shelves full of Hugos and/or Nebulas. I have equally brilliant writer/editor friends who’ve never even been nominated. As awards season approaches, more and more authors are posting a list of their award-eligible work from the previous year.

As awards season approaches, more and more authors are posting a list of their award-eligible work from the previous year.