Alien of Extraordinary Ability? Migration in SFF and in my Life – Bogi Takács

As we get to the last few of these guest blog posts, I’m trying to look ahead to the process of pulling everything together for Invisible 2. Like last year, my plan is to do an electronic anthology, and to donate any profits to a relevant cause (which I’ll be discussing with contributors.) The anthology will probably have the same $2.99 price point. I don’t have a release date yet, but I’ll share more info as things progress.

For today, I’m happy to welcome Bogi Takács to the blog to talk about migration/migrants in SFF, and in eir life. It’s educational and eye-opening, to say the least.

I’m an autistic trans person from a non-Western country where I also belong to an ethnic minority. I could write about many, many intersections, and how my lived experience is or is not represented in SF. Yet for this essay I chose to talk about something people might not consider about me: the experience of being a migrant.

Before we begin, a terminological note: I really do prefer the term “migrants” to “immigrants”. First, “immigrants” assumes that your destination is more important than your origin. (It is, not surprisingly, common in US-centric discourse.) Second, “immigrant” often has a precise legal definition that many migrants are literally not able to claim.

With that in mind, people migrate all the time: they immigrate, from one perspective, they emigrate, from another. I’ve lived in Hungary (where I was born), in Austria, in Norway, and I’ve recently moved to the United States. I have experienced a bewildering range of reactions and treatment, some of which I would not even describe here, because I developed quite an amount of self-censorship in the process.

As a migrant academic, I often find myself in curious legal categories where I can’t even claim the legal protections afforded to people with immigrant status, with many if not most of the downsides. Right now, I cannot earn any money outside campus – I even had to turn down the $10 Jim offered to include this essay in Invisible 2.

On the online SFF scene, I am usually seen as the ethnic, religious, gender, sexual minority person – take your pick! People don’t see me as a migrant, and yet this is possibly what defines my day to day experience the most. I now live in a small liberal town where I can literally go around being draped in a Pride flag and random strangers will cheer me on. (For the record, I tried this. I also tried this in Hungary. DO NOT TRY THIS IN HUNGARY.) People are sometimes perplexed by my gender, but unlike in my country of origin, I haven’t experienced physical violence. Americans also have trouble believing that I have ever been the target of physically violent racism, because they categorize and treat me as white.

Warning: self-exoticization follows!

By contrast, what I experience all the time is being the strange foreigner [sic], being from somewhere else with exotic customs [sic] – and often not being taken at face value when I talk of my experience having lived there. I have a weird accent [sic]. (Actually I have a “weird accent” in any language due to being autistic, but most Americans don’t know this.)

People try to be nice: “I have been to your country as a tourist, it’s such an amazing place!” …Umm, yeah, guess why I’m not there.

To see where migration fits into my experience of SFF in particular, and why I feel invisible as a migrant, we need to start quite far, both in space and in time. As a multiply marginalized person, I discovered thanks to the Vienna Public Library that there was a vast amount of literature beyond the Western literary canon that really resonated with me. Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o’s work – both fiction and nonfiction – in particular was eye-opening to me, especially Matigari and Decolonising the Mind. I discovered the solidarity of the marginalized that had up till that moment been nothing more than a dated Communist slogan from my childhood.

This was before I got summarily thrown out of the Vienna Public Library and my account cancelled because as a migrant I didn’t have just the right legal document! (Even though I was in Austria perfectly legally.) …My life was changed regardless.

I had been a voracious SFF reader since early childhood – my parents were both agricultural engineers at that time and heavily into SFF. In Hungary this is not a particularly subcultural activity, SFF is much more a part of mainstream literature and a lot of people read SFF who would not be considered part of core fandom in the US. The definitive Hungarian print SFF magazine, Galaktika, has a print circulation similar to the big three print American SFF magazines, while Hungary has a population half the size of the New York City metropolitan area!

As a child I read many, many Soviet and other Eastern bloc SF works where people of different cultures and races worked together – this was a trope of Communist propaganda, the “friendship of the peoples” (népek barátsága in Hungarian, druzhba narodov in Russian). But these works were written by ethnic majority people, and from a position of power – in the case of ethnic Russian authors, even a position of colonizing power.

The friendship of the peoples was, in practice, very limited. It could not include Jews. It could not include Romani or Beás people. It could not include queer people. Trans people could only be aliens – oddly, they could be aliens. Religious people were obviously out – religion was the opiate of the peoples, as Marx had put.

When I started to read in English, what could I obtain in Hungary? Novels from the Asimov-Bradbury-Clarke triumvirate, some William Gibson, and precious little else… basically the same American authors that I could already read in Hungarian translation. While I greatly admired Bradbury, his semi-autobiographic Dandelion Wine was so different from my own childhood experience that I literally cried from frustration. (Gibson was different, but that’s a topic for another time.) I came to understand why Dandelion Wine was never published in Hungary!

So when I discovered online short SFF in English, I was amazed. There were so many people, from all over the world, who were writing from their own perspective, about their own experience, and I could obtain vast amounts of this stuff free of charge! I could actually talk to the authors and they responded! At the risk of sounding trite: this was, in effect, the friendship of the peoples.

Yet almost immediately thereafter I discovered a curious gap: a lot of the American SFF discourse, even very “progressive” and left-wing discourse, seemed to ignore that migrants existed. Again, the friendship of the peoples didn’t seem to extend very far… For instance, I was baffled when Ekaterina Sedia was dismissed by Wiscon organizers who tried to shoehorn the American immigrant experience into, at best, an “ESL workshop”. (Because professionally published writers like her need an ESL workshop – how patronizing is that?)

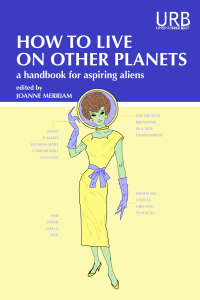

The first anthology of immigration-themed SFF, How to Live on Other Planets (ed. Joanne Merriam) is coming out just now, and it’s reprints-only and had a royalties-only payrate. (Not that I can get paid, anyway!) Despite that, the lineup is stellar, because many, many writers are migrants themselves, or the children of migrants, and are eager for their words being heard. It is also striking that a lot of the best migrant writing seems to come from semi-pro SFF or literary fiction markets, not the core pro SFF venues.

The first anthology of immigration-themed SFF, How to Live on Other Planets (ed. Joanne Merriam) is coming out just now, and it’s reprints-only and had a royalties-only payrate. (Not that I can get paid, anyway!) Despite that, the lineup is stellar, because many, many writers are migrants themselves, or the children of migrants, and are eager for their words being heard. It is also striking that a lot of the best migrant writing seems to come from semi-pro SFF or literary fiction markets, not the core pro SFF venues.

Full disclosure: I have a poem in How to Live on Other Planets. It’s about my country of origin, so might be a bit out of place, but it does examine Hungary from the PoV of an outsider – an alien.

I am, right now, literally an alien – probably the most annoying kind, the “non-resident alien”. (This is the actual legal term.) I have to pay taxes, yet I cannot vote.

For further American legal terms to baffle and entertain, I also recommend you look up “alien of extraordinary ability”. I’m not an alien of extraordinary ability. I’m just a quirky and mild-mannered everyday person who sometimes writes poetry. I’m also very loud and paste myself all over the internet, so if I remain invisible, that’s not on me.

Part of my loudness consists of providing story recommendations to every passerby on Twitter who just as much asks an idle question. Therefore, I close this essay with an amount of free, online SFF story recommendations on the theme of migration!

- Ken Liu, an immigrant from China to the US, has some heartbreaking stories about migration – many of you have probably read the award-winning Paper Menagerie, but I’d also recommend To the Moon and All the Flavors: A Tale of Guan Yu, the Chinese God of War, in America.

- Zen Cho, originally from Malaysia and living in the UK, has recently had a short story collection published, Spirits Abroad. I loved it to bits. Not all stories are available online, but for example you can read 起狮,行礼 (Rising Lion—The Lion Bows), with an all-migrant cast of protagonists, or The Four Generations of Chang E.

- Arab-Canadian author Amal El-Mohtar has a powerful story about immigrating as a child: The Truth about Owls, originally published in Kaleidoscope (ed. Julia Rios and Alisa Krasnostein).

- Three Immigrations is a long poem by Rose Lemberg that’s one of the best poetic treatments of the topic I’ve come across.

Bogi Takács is a neutrally gendered Hungarian Jewish person who’s recently moved to the US. E works in a lab and writes speculative fiction and poetry in eir spare time. Eir writing has been published in venues like Strange Horizons, Apex, Scigentasy, GigaNotoSaurus and other places. You can follow em on Twitter, where e tweets as @bogiperson, with semi-daily recommendations of #diversestories and #diversepoems that are regularly collected on eir website.

In contrast to Heroes, The Sparrow, a novel by Mary Doria Russell, has as its protagonist Father Emilio Sandoz, a brilliant Puerto Rican linguist who is of Taino and Spanish background. The Sparrow is one of my all-time favorite books, and Emilio Sandoz is one of my favorite characters, and one with whom I identify closely. Not to take away from the novel, which I think tells an incredible story, but the fact that the portion of the novel that takes place on Earth takes place in Puerto Rico, and that the main character is Puerto Rican is part of why I love it so much. Finally, someone who looks like me. Someone who lived in the same place my mother grew up, where her parents came from, a place that I was connected to.

In contrast to Heroes, The Sparrow, a novel by Mary Doria Russell, has as its protagonist Father Emilio Sandoz, a brilliant Puerto Rican linguist who is of Taino and Spanish background. The Sparrow is one of my all-time favorite books, and Emilio Sandoz is one of my favorite characters, and one with whom I identify closely. Not to take away from the novel, which I think tells an incredible story, but the fact that the portion of the novel that takes place on Earth takes place in Puerto Rico, and that the main character is Puerto Rican is part of why I love it so much. Finally, someone who looks like me. Someone who lived in the same place my mother grew up, where her parents came from, a place that I was connected to.

When I read Christie as a kid, I didn’t much like the Marple books, yet all these years later, I found myself captivated by this smart “elderly spinster.” Odd. Then I realized what had happened: I got old. Maybe not as old as Miss Marple, who is probably somewhere between 60 and 80, depending on the book, but definitely not young, not cute, not the object of men’s desire. All of a sudden, the idea that the main actor in a story could be the older woman appealed to me.

When I read Christie as a kid, I didn’t much like the Marple books, yet all these years later, I found myself captivated by this smart “elderly spinster.” Odd. Then I realized what had happened: I got old. Maybe not as old as Miss Marple, who is probably somewhere between 60 and 80, depending on the book, but definitely not young, not cute, not the object of men’s desire. All of a sudden, the idea that the main actor in a story could be the older woman appealed to me.

Next, I found Marge Piercy’s He, She, and It. Piercy brings the golem legend into science fiction by playing on its parallel to the android, with plenty of Jewish culture and history to provide setting, context, and flavor. Some of it was the result of extensive historical research, but some of it was the kind of flavor that only experience can provide. Someone else in the world knew what it was like to grow up with a grandmother like mine, with holidays I celebrated. I’d been the only Jewish kid in my class—for five years, the only one in my whole school—so I’d never had a friend who grew up with the same rituals and references I did. To find it in a book was to find a friend.

Next, I found Marge Piercy’s He, She, and It. Piercy brings the golem legend into science fiction by playing on its parallel to the android, with plenty of Jewish culture and history to provide setting, context, and flavor. Some of it was the result of extensive historical research, but some of it was the kind of flavor that only experience can provide. Someone else in the world knew what it was like to grow up with a grandmother like mine, with holidays I celebrated. I’d been the only Jewish kid in my class—for five years, the only one in my whole school—so I’d never had a friend who grew up with the same rituals and references I did. To find it in a book was to find a friend.