The Double Standards of Diversity – Dennis R. Upkins

This post has been removed per the author’s request. -Jim

This post has been removed per the author’s request. -Jim

Cat Rambo, in addition to having the coolest name ever, has been an active part of SF/F for about as long as I can remember. She’s served in SFWA, and is currently running for president of the organization. She edited Fantasy Magazine. She’s a prolific author. And she has the best hair! I’m happy to welcome her to the blog to talk about her experiences as an “older” female writer in the genre.

You can check out her new book Beasts of Tabat on Amazon or Wordfire, or read more about it on her website.

A year or so ago, I celebrated my 50th birthday. I did it wonderfully, with food and friends and all sorts of festivities, but at the same time, my inner teen kept eying that number and going OMGWTFBBQ.

If you are beyond your teenage years, you know what I mean, because all of us are, to one extent or another, significantly younger in our heads than our exteriors may indicate. My mother confirms that it’s just as true in one’s 70s.

I do find my reading habits changed a little. My stance on romance nowadays has shifted. It sometimes makes me a little impatient, a little get-on-with-it when it’s not interesting, and when it is badly written. I find simplistic stuff unsatisfying unless it is absolutely, beautifully wrought. I don’t mind unhappy endings as long as they resonate and I can tell.

But it’s when I write that I sometimes feel my age, not in a bad way. Not in a bad way at all. But rather I understand things better than I used to. I have more grasp of how to flip oneself into the opposing perspective, so I can better understand what’s on the other side of a debate. I hate to call it wisdom, but yes, I have learned a few things, and because I’ve read deeply and also worked in some people-skills-intensive position, I’ve got enough of it to know I am not wise at all, and that’s farther along than some people have gotten.

I’ve come to the point where I understand something of why I write, and a little of what I want to say. I like that. And I know people better now, and that helps me create interesting characters. The novel that’s coming out, Beasts of Tabat, features a middle-aged female gladiator and a teenage shapeshifter. That’s a pair of protagonists a bit outside the norm, and I think that it’s experience that let me come up with Bella Kanto and Teo.

I’ve come to the point where I understand something of why I write, and a little of what I want to say. I like that. And I know people better now, and that helps me create interesting characters. The novel that’s coming out, Beasts of Tabat, features a middle-aged female gladiator and a teenage shapeshifter. That’s a pair of protagonists a bit outside the norm, and I think that it’s experience that let me come up with Bella Kanto and Teo.

At the same time, as an older female writer, I’m also conscious that I’m part of a demographic traditionally dismissed, particularly in writing. I am one of that mob of dammed scribbling women that Nathaniel Hawthorne deplored. And I am aware that much of that mob has been allowed to fade from historical memory, something I see happening to some of the women in the speculative field before me right now. Something that I worry will happen to me.

There’s been lots of sturm und drang about an idea Tempest Bradford proposed, that people try one year of reading outside the standard category, and I will take it one step further: if you are an adventurous reader who likes challenging yourself, spend a year reading from outside that category, but only books that are 30+ years old, preferably even older. You’ll find the chase illuminating. You’ll find influences. You’ll find writers talking to each other, an endless call and answer throughout literature that every writer takes part in, and sometimes those conversations will startle you in their modernity. You’ll find people that maybe other people tried to erase, or maybe the hegemony just wasn’t set up to perpetuate their name — it doesn’t really matter. What matters is the renewal of energy in their names. Read in other cultures, other times.

Younger writers will find inspiration there, older writers comfort as well. And the fuel to keep going — at least that’s one of the ways I feed my own fires.

I do hope you’ll read my own new novel before embarking on the course I advise

Good writing/reading to you all.

Cat Rambo lives, writes, and teaches by the shores of an eagle-haunted lake in the Pacific Northwest. Her fiction publications include stories in Asimov’s, Clarkesworld Magazine, and Tor.com as well as three collections and her latest work, the novel Beasts of Tabat. Her short story, “Five Ways to Fall in Love on Planet Porcelain,” from her story collection Near + Far (Hydra House Books), was a 2012 Nebula nominee. Her editorship of Fantasy Magazine earned her a World Fantasy Award nomination in 2012. She is the current Vice President of the Science Fiction and Fantasy Writers of America. For more about her, as well as links to her fiction, see http://www.kittywumpus.net.

This rant list has been brought to you by a few comments on this blog post, and by observations about the internet in general. Before jumping in to immediately offer advice on all the things, please consider asking yourself the following questions. Thank you.

And yeah, I get the potential irony of giving advice about asking questions before giving advice. I also think there’s a huge difference between sharing my thoughts in a blog post and jumping into other conversations to tell an individual what you think they should do.

Did this person ask for advice?

Hint: Posting about something on the internet is not the same as asking for advice. Requests for advice usually involve phrases like “What do you think I should do?” or “I need advice.”

Do you think your advice is something this person hasn’t already heard?

Hint: I’ve been diabetic for 16 years. If you’re neither diabetic nor a doctor, I probably know more about my disease than you do. I’ve read the books, heard the advice, followed the online discussions, talked to the doctors, and so on. On a similar note, someone who’s overweight has probably already heard your advice to exercise more. Someone with depression has already heard your advice to “just think positive!”

Do you know enough about this person’s situation to give useful advice?

Hint: Telling someone with financial problems to get rid of their credit cards isn’t going to cut it if they’re currently paying legal fees following a divorce, are underwater in their mortgage, and just got laid off from work.

Are you more concerned with helping or with fixing the person so they’ll stop making you uncomfortable?

Hint: People talk about their problems for a range of reasons. To vent, to process their own feelings, to connect with others and know they’re not alone… If you genuinely want to help, great—but in many cases, giving advice isn’t the way to do that.

Are you more concerned with helping or with looking clever? Are you willing to be told your advice is unwanted?

Hint: If the person in question says they’re not interested in your advice and you respond by getting huffy or defensive or going Full Asshole, then this isn’t about the other person. This is about you and your ego. Take your ego out for ice cream, and stop adding to other people’s problems.

Are you sharing what worked for you or telling the person what they should do?

Hint: There’s a difference between “This is something that helped me,” “This is something you might try,” and “This is what you should do.” For me personally, the first option is easier to hear than the second, and the third usually just pisses me off. But also be prepared to hear that the person doesn’t want your advice, no matter how you phrase it.

Do you know what “giving advice” looks like?

Hint: I wouldn’t have thought this one was necessary. Then I got the commenter responding to one of my posts on depression by telling me, “Listen to your inner self and make it your outer self” and insisting he wasn’t giving me advice. He was just “stating an opinion.” Dude, if you’re telling someone what to do, you’re giving advice. If you’re getting huffy about it just being your opinion, you may also be acting like an asshole.

Have you asked whether the person wants your advice?

Hint: If you’re not sure what someone wants, asking is a pretty safe way to go.

#

I’m not saying you should never offer advice. A few days ago, I left a comment on someone’s Facebook post where she was questioning whether she should bother trying to get her book published. I offered my experience, disagreed with a writing-related myth she referenced, pointed to several options that had worked for myself or other writers, and acknowledged that my advice might or might not be helpful for her particular situation.

But I have zero patience these days for the useless, knee-jerk advice that comes from a place of ego and cluelessnes.

Earlier this month, Libriomancer [Amazon | B&N | Mysterious Galaxy] was a Kindle Daily Deal, meaning Amazon was selling the e-book for a mere $1.99. This was the first time one of my books had been selected for the KDD program, and I have to say, it was pretty sweet. But how much of an impact does that $1.99 day really have?

I’ll probably never have exact numbers. These sales will show up on my next royalty statement, which covers January – June of this year, but doesn’t break things down by day or week.

Here’s what I do know…

1. Once Amazon drops the price, most other online retailers follow suit. Soon after I posted about the Kindle Daily Deal, I realized the book was also on sale at Barnes & Noble. Then people mentioned Google Play and iBooks. They all seem to monitor and price-match, which means the book was on sale pretty much across the board…at least in the U.S. Alas, Europe and most other non-U.S. ebook sellers didn’t get in on the action.

2. Libriomancer was, at least for one day, outselling Fifty Shades of Grey.

3. We probably sold >1000 ebooks on Amazon alone. But wait, didn’t I just say I wouldn’t get numbers until my next royalty statement? Well, yes. But I do have the ability to pull up my Amazon affiliate account and see how many copies sold through that link. About 350 or so people bought Libriomancer through my site and links. My friend Howard Tayler (of Schlock Mercenary fame) was kind enough not only to mention the sale, but also to email me afterward and let me know he’d had close to 400 sales through his post. Given that Amazon was also marketing the book, and other folks were signal-boosting, I think 1000+ is a reasonable guess.

4. Apparently Libriomancer is a Sword & Sorcery book. This was news to me. But who am I to argue with this screencap?

5. I have absolutely wonderful friends and fans. I was blown away by how many people signal-boosted the sale. Thank you all so much for the support and word-of-mouth.

6. I’m still addicted to checking my Amazon rankings. Most days, I’ve gotten to where I don’t need to check in to see if my sales rank has gone up or down, or if anyone’s left a new review, or whatever. But I was clicking Refresh all day to see what kind of impact the sale would have. At one point, Libriomancer was #1 in two different categories, and #16 among all paid Kindle books, which is pretty sweet.

This also put the book near the top of Amazon’s “Movers and Shakers” for the day:

7. It boosts sales of other books in the series, too. Neither Codex Born nor Unbound saw the same level of sales, but the Amazon rank for both of those books ended up in the four-digit range, meaning sales were above-average for them as well. Probably not a huge number of sales, but definitely better than nothing! Hopefully there will be some longer-term sales too as people finish reading Libriomancer.

8. A few weeks later, I’ve got 24 new Amazon reviews for Libriomancer. I don’t know if those extra reviews will help to sell more books, but it’s nice to see, and it means at least some of the people who picked up the book also read and enjoyed it. Yay!

9. Amazon pushes and markets its KDD books. As one of my fellow authors put it, this is a situation where the author gets the benefits of Amazon’s market and advertising power. They promote their Kindle Daily Deals, and while I don’t know how much that helps, it’s certainly a significant boost.

#

Thanks again to everyone who signal-boosted, and to all of the readers who shelled out $2 to try the book. I hope you enjoy it!

I’ll probably check back in later this year once I’ve seen royalty statements, and can compare this six-month window to prior royalty periods. In the meantime, I’d love to hear from other authors who’ve done the KDD thing. How did your experience compare to mine? Any additional insight or information you can share?

Friday loves fan art…

I have a guest blog post up at Amazing Stories, reminiscing about WindyCon.

I’m also part of the Mind Meld at SF Signal, talking about funny short stories in SF/F.

And if that’s not enough, I chatted with the folks at Beyond the Trope, and that podcast just went live.

Finally, Klud the goblin sent out another newsletter earlier this month.

Thus endeth the linkspam.

As we get to the last few of these guest blog posts, I’m trying to look ahead to the process of pulling everything together for Invisible 2. Like last year, my plan is to do an electronic anthology, and to donate any profits to a relevant cause (which I’ll be discussing with contributors.) The anthology will probably have the same $2.99 price point. I don’t have a release date yet, but I’ll share more info as things progress.

For today, I’m happy to welcome Bogi Takács to the blog to talk about migration/migrants in SFF, and in eir life. It’s educational and eye-opening, to say the least.

I’m an autistic trans person from a non-Western country where I also belong to an ethnic minority. I could write about many, many intersections, and how my lived experience is or is not represented in SF. Yet for this essay I chose to talk about something people might not consider about me: the experience of being a migrant.

Before we begin, a terminological note: I really do prefer the term “migrants” to “immigrants”. First, “immigrants” assumes that your destination is more important than your origin. (It is, not surprisingly, common in US-centric discourse.) Second, “immigrant” often has a precise legal definition that many migrants are literally not able to claim.

With that in mind, people migrate all the time: they immigrate, from one perspective, they emigrate, from another. I’ve lived in Hungary (where I was born), in Austria, in Norway, and I’ve recently moved to the United States. I have experienced a bewildering range of reactions and treatment, some of which I would not even describe here, because I developed quite an amount of self-censorship in the process.

As a migrant academic, I often find myself in curious legal categories where I can’t even claim the legal protections afforded to people with immigrant status, with many if not most of the downsides. Right now, I cannot earn any money outside campus – I even had to turn down the $10 Jim offered to include this essay in Invisible 2.

On the online SFF scene, I am usually seen as the ethnic, religious, gender, sexual minority person – take your pick! People don’t see me as a migrant, and yet this is possibly what defines my day to day experience the most. I now live in a small liberal town where I can literally go around being draped in a Pride flag and random strangers will cheer me on. (For the record, I tried this. I also tried this in Hungary. DO NOT TRY THIS IN HUNGARY.) People are sometimes perplexed by my gender, but unlike in my country of origin, I haven’t experienced physical violence. Americans also have trouble believing that I have ever been the target of physically violent racism, because they categorize and treat me as white.

Warning: self-exoticization follows!

By contrast, what I experience all the time is being the strange foreigner [sic], being from somewhere else with exotic customs [sic] – and often not being taken at face value when I talk of my experience having lived there. I have a weird accent [sic]. (Actually I have a “weird accent” in any language due to being autistic, but most Americans don’t know this.)

People try to be nice: “I have been to your country as a tourist, it’s such an amazing place!” …Umm, yeah, guess why I’m not there.

To see where migration fits into my experience of SFF in particular, and why I feel invisible as a migrant, we need to start quite far, both in space and in time. As a multiply marginalized person, I discovered thanks to the Vienna Public Library that there was a vast amount of literature beyond the Western literary canon that really resonated with me. Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o’s work – both fiction and nonfiction – in particular was eye-opening to me, especially Matigari and Decolonising the Mind. I discovered the solidarity of the marginalized that had up till that moment been nothing more than a dated Communist slogan from my childhood.

This was before I got summarily thrown out of the Vienna Public Library and my account cancelled because as a migrant I didn’t have just the right legal document! (Even though I was in Austria perfectly legally.) …My life was changed regardless.

I had been a voracious SFF reader since early childhood – my parents were both agricultural engineers at that time and heavily into SFF. In Hungary this is not a particularly subcultural activity, SFF is much more a part of mainstream literature and a lot of people read SFF who would not be considered part of core fandom in the US. The definitive Hungarian print SFF magazine, Galaktika, has a print circulation similar to the big three print American SFF magazines, while Hungary has a population half the size of the New York City metropolitan area!

As a child I read many, many Soviet and other Eastern bloc SF works where people of different cultures and races worked together – this was a trope of Communist propaganda, the “friendship of the peoples” (népek barátsága in Hungarian, druzhba narodov in Russian). But these works were written by ethnic majority people, and from a position of power – in the case of ethnic Russian authors, even a position of colonizing power.

The friendship of the peoples was, in practice, very limited. It could not include Jews. It could not include Romani or Beás people. It could not include queer people. Trans people could only be aliens – oddly, they could be aliens. Religious people were obviously out – religion was the opiate of the peoples, as Marx had put.

When I started to read in English, what could I obtain in Hungary? Novels from the Asimov-Bradbury-Clarke triumvirate, some William Gibson, and precious little else… basically the same American authors that I could already read in Hungarian translation. While I greatly admired Bradbury, his semi-autobiographic Dandelion Wine was so different from my own childhood experience that I literally cried from frustration. (Gibson was different, but that’s a topic for another time.) I came to understand why Dandelion Wine was never published in Hungary!

So when I discovered online short SFF in English, I was amazed. There were so many people, from all over the world, who were writing from their own perspective, about their own experience, and I could obtain vast amounts of this stuff free of charge! I could actually talk to the authors and they responded! At the risk of sounding trite: this was, in effect, the friendship of the peoples.

Yet almost immediately thereafter I discovered a curious gap: a lot of the American SFF discourse, even very “progressive” and left-wing discourse, seemed to ignore that migrants existed. Again, the friendship of the peoples didn’t seem to extend very far… For instance, I was baffled when Ekaterina Sedia was dismissed by Wiscon organizers who tried to shoehorn the American immigrant experience into, at best, an “ESL workshop”. (Because professionally published writers like her need an ESL workshop – how patronizing is that?)

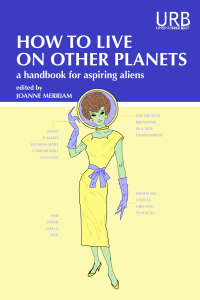

The first anthology of immigration-themed SFF, How to Live on Other Planets (ed. Joanne Merriam) is coming out just now, and it’s reprints-only and had a royalties-only payrate. (Not that I can get paid, anyway!) Despite that, the lineup is stellar, because many, many writers are migrants themselves, or the children of migrants, and are eager for their words being heard. It is also striking that a lot of the best migrant writing seems to come from semi-pro SFF or literary fiction markets, not the core pro SFF venues.

The first anthology of immigration-themed SFF, How to Live on Other Planets (ed. Joanne Merriam) is coming out just now, and it’s reprints-only and had a royalties-only payrate. (Not that I can get paid, anyway!) Despite that, the lineup is stellar, because many, many writers are migrants themselves, or the children of migrants, and are eager for their words being heard. It is also striking that a lot of the best migrant writing seems to come from semi-pro SFF or literary fiction markets, not the core pro SFF venues.

Full disclosure: I have a poem in How to Live on Other Planets. It’s about my country of origin, so might be a bit out of place, but it does examine Hungary from the PoV of an outsider – an alien.

I am, right now, literally an alien – probably the most annoying kind, the “non-resident alien”. (This is the actual legal term.) I have to pay taxes, yet I cannot vote.

For further American legal terms to baffle and entertain, I also recommend you look up “alien of extraordinary ability”. I’m not an alien of extraordinary ability. I’m just a quirky and mild-mannered everyday person who sometimes writes poetry. I’m also very loud and paste myself all over the internet, so if I remain invisible, that’s not on me.

Part of my loudness consists of providing story recommendations to every passerby on Twitter who just as much asks an idle question. Therefore, I close this essay with an amount of free, online SFF story recommendations on the theme of migration!

Bogi Takács is a neutrally gendered Hungarian Jewish person who’s recently moved to the US. E works in a lab and writes speculative fiction and poetry in eir spare time. Eir writing has been published in venues like Strange Horizons, Apex, Scigentasy, GigaNotoSaurus and other places. You can follow em on Twitter, where e tweets as @bogiperson, with semi-daily recommendations of #diversestories and #diversepoems that are regularly collected on eir website.

I remember being a child and getting bags full of plastic Cowboys and Indians–similar to green plastic soldiers, but these came in all colors. The Indians all had bows and arrows and feathered headdresses and buckskins. I never thought much about it, but looking back, my sense was that Cowboys and Indians were something out of history. Almost a mythical thing, from hundreds of years ago.

In Boy Scouts, I was a member of the Order of the Arrow. It was an honor to be voted into this group by my troop, and I remember thinking how cool the Native American lore and ceremonies were. I spent several years as a part of our ceremonies team. Eventually, I remember starting to feel uncomfortable, and asking if we weren’t being disrespectful. I was told that our lodge had worked to research historically accurate regalia, and that we’d worked with local tribes to make sure we were being respectful. At the time, I was satisfied. Looking back, I find it interesting that we never actually spoke to or interacted with anyone with native heritage during our time in OA.

My thanks to Jessica McDonald for sharing her story and perspective here. There’s so much here and in the other guest posts that I wish I’d learned as a kid…

In 1889, the US government opened up Indian Territory for white settlers in an event called the Oklahoma Land Rush. Fifty thousand settlers homesteaded on over two million acres of Unassigned Lands. Unassigned, of course, meant appropriated from Native tribes.

A hundred years after the Land Rush, I was a second grader at Carney Elementary School in central Oklahoma. Carney is the kind of town that small doesn’t begin to describe. We didn’t even have a stoplight to brag about. Farms, baseball, and ubiquitous red soil were about the extent of Carney. For the Land Rush celebration, my school did a re-enactment. White kids played settlers, triumphantly surging over the territory line to claim their homestead—a mark of prosperity and hope.

Native kids played dead Indians, lying prone on the ground.

I stood there, unsure of what to do. You see, I’m mixed race—Cherokee and white. I didn’t know where to go. My teacher asked me which side I’d like to be on.

I told her the settlers.

And as an eight-year-old, why wouldn’t I choose the settlers? They were pioneers, exploring and shaping history. Of course I wanted to be part of the victors. Of course I wanted to be white. I knew my family, but when I looked to the culture around me, the media I consumed, all my heroes were white (and male). That was my reference point for greatness.

I’m way past second grade now, but not much as changed. Sci-fi and fantasy—still my favorite genres—seldom offer more than tropes for Native characters. Let’s take a look at James Cameron’s Avatar. Set on a futuristic death planet where everyone is still inexplicably white, the Na’vi are clearly based on indigenous people and presented as the Noble Savage. They are held up as the ideal, “pure”, and quite literally connected to their planet. And yet, it takes a white dreamwalker to save them, because at the end of the day, they are still savages; they do not possess the sophistication to fight the invaders alone.

The weird Western novella Sheep’s Clothing by Elizabeth Einspanier utilizes another trope—the Mystical Indian. Half-Indian character Wolf Cowrie is a gunslinger and half-skinwalker that uses his shamanistic powers to fight vampires. The problem with this is that it reduces Native characters to one (false) aspect: their unequivocal badassed-ness, a nature derived from a history filled with war and mysterious magical abilities.

Westerns used the Drunk Indian and Red Devil tropes, but sci-fi and fantasy utilize stereotypes like the Noble Savage and Mystical Indian in a way that’s arguably worse. These tropes, which simultaneously glorify and erase Native identity, are what’s called positive discrimination, and it’s more insidious precisely because, on its face, it appears flattering. “Look at how honorable and incredible these Natives are! We should strive to be more like them.” Even Star Trek fell into this—in the episode “The Paradise Syndrome,” Kirk, Spock, and McCoy encounter an Earth-like planet… with Native people that are not only blends of completely different tribes, but also primitive and uncivilized, despite living in the twenty-third century. Oh, but these Natives are definitely in harmony with nature, and are romanticized for it.

All this does is add to the chasm of otherness; these tropes don’t seek to understand or accurately portray indigenous people, but only use us as one-dimensional morality points or exciting badasses. Sometimes we get to stretch the limits, and we’re hypersexualized instead (Tiger Lily, Pocahontas, any Indian Princess trope).

The proof is in the costuming. Rarely do we see even “positive” portrayals of Natives in anything other than buckskins, beads, and feathers. We are homogenized to the point that the Plains tribes, with headdresses and horsemanship, are the representatives of all indigenous people. Never mind that Algonquin tribes, who lived in lands dominated by forests, had no use for horses. Never mind that the Salish peoples wore outfits woven from cedar and spruce instead of long, feathered accouterments.

A Cree friend of mine encountered a woman in a critique group who had a Shawnee character that was a horse whisperer. When my friend pushed her on why this character was so connected to horses, the (white) woman responded that it was “in his heritage.” Because being Native clearly means you speak horse.

My brother has been asked if he can ride horses without a saddle and if he smokes peyote. During a particularly asinine line of questioning about whether he lived in “modern” accommodations, he shot back, “Yes, because I live in 2014, not 1865.” His tipi has a mortgage, folks.

I’ve read work by otherwise intelligent, compassionate authors who twist revered Native spirits into European-based demons bent on destruction just to fill a plot point and without any regard for the religious traditions behind those spirits.

I don’t speak to animals. I kill plants just by looking at them, and I don’t feel profoundly connected to the earth. I can’t tell the future and I don’t have some sort of sixth sense about otherworldly things. I sure as hell don’t speak in broken English. Relatable Native characters in sci-fi and fantasy are few in far between. Mostly, I see variations on tropey themes. What’s most painful about this in sci-fi and fantasy is that these are genres about the possible. SF/F is supposed to be the genre where the marginalized are heard. We get worlds where magic is real, where we travel to far-away galaxies, where miracles happen. But not where indigenous peoples can escape their stereotype boxes.

And why not? Sci-fi and fantasy are written by people in today’s world, and what we have today is a major football team using a racial slur as their name. We have white University of North Dakota students proudly proclaiming that they are “Siouxper Drunk”; Injun Joe from Tom Sawyer; Disney’s Pocahontas and Peter Pan; NDNs (played by Italian Americans) crying over pollution.

We have NDN heroes that are literally red.

To add insult to injury, even the problematic Native roles in film and TV were largely portrayed by white people. It wasn’t until 1998 with Smoke Signals that we got the first feature-length film by Natives. And yet, in 2013, we still had Johnny Depp playing Tonto and The Lone Ranger winning an Oscar for costuming based on a painting that was itself based on stereotypes. We still have white washing of Tiger Lily.

If you’re thinking, hey, man, it’s just comic books and movies, it’s not like it’s real life—consider the impact this has on young Native and mixed-race kids. Consider why I wanted to be on the white side as a child. I had no reference for modern Natives. I had no role models, no fictional characters to inspire me. All I had were people in revealing buckskins with tomahawks and bows.

Studies show that when Native kids see these harmful stereotypes, their self-esteem suffers, along with their belief in community and their own ability to achieve great things. There’s a danger when you don’t see yourself represented in your culture’s art; there’s an even greater danger when your only representation is fraught with negative messaging and teaches you that you do not belong in this world. You’re a thing of the past, a ghost, a myth.

We’ve got a few reasons to hope the tide is changing. Faith Hunter’s Jane Yellowrock series and Patricia Briggs’s Mercy Thompson series turn the Mystical Indian trope on its head, with nuanced and dynamic Native heroines. Adam Beach, a Saulteaux actor famous for his roles in Smoke Signals, Flags of Our Fathers, and Windtalkers, refuses parts that perpetuate these stereotypes, and his work offers hope for better representation. Lakota rapper Frank Waln creates music that speaks to growing up Native, and advocates for indigenous voices to be heard. Last year, the Senate confirmed Diane Humetewa as the nation’s first Native American woman federal judge.

This year, we even have two sci-fi films that are breaking out of the Native trope mold. Sixth World, written and directed by Navajo woman Nanobah Becker, is based on the Navajo creation story. Legends of the Sky is written and directed by a white man, but is set in the Navajo Nation and features a mostly Native cast.

It’s not nearly enough, but it’s sure as hell better than playing dead on the ground.

Jessica McDonald lives in Denver and is a writer, technophile, gamer, and all-round geek. She serves as the marketing director for SparkFun Electronics in Boulder. She earned her Master’s degree from the University of Denver and holds undergraduate degrees from The Pennsylvania State University, and has worked for everything from political campaigns to game design companies. She has published original research on online user behavior, and writes about marketing, technology, women in STEM, and diversity in media. Her background in the technology and defense industries makes her an insightful critic of gender representation in fiction, film, video games, and comics. Growing up looking white but with Cherokee heritage, she also advocates for representation of people of color and mixed-race characters. Jessica has presented at SXSW Interactive, Shenzhen Maker Faire, American Public Health Association’s national conference, and Pikes Peak Writers Conference. She is the author of the urban fantasy novel BORN TO BE MAGIC and currently is writing a YA novel based on Navajo mythology. Find her on Twitter or on her website.

Sarah Chorn is the host of the Special Needs in Strange Worlds column at SF Signal, and has become an important voice in the conversation about disability in genre. If you’ve been appreciating these guest blog posts, you should check out her column as well, where she’s hosted a wide range of authors talking about disability.

My brother Rob has a condition called Agenesis of the Corpus Callosum, as well as spina bifida. His life has been one very, very long struggle against himself, the world that doesn’t understand him, and sometimes his own family. Rob functions a lot like a person with Asperger’s. His spina bifida has relegated him to a wheelchair. Currently, due to seizures, he can’t read anymore.

Rob was the person who really got me into the genre. When I was a horrible teenager, it was Rob who got me to read The Wheel of Time, Dragonlance, Memory, Sorrow, and Thorn, and A Song of Ice and Fire. It was Rob who traded books with me, and spent hours talking to me about worlds, plots and characters.

We can all blame my brother for my enthusiasm for this genre.

It was also Rob who taught me that reading is more than just a hobby. For him, it’s a way for others to understand how he lives and interprets the world around him. It is also a way for him to sort of take a vacation from his body, and his problems for a time. Reading wasn’t just fun, but an exercise and an education for him, and for me.

It is important to remember that books aren’t just pretty words strung together in an entertaining fashion. They are windows into souls, and looking glasses into the world around us. These books tell stories about lives and conditions that we might not be able to understand or experience on our own. They educate us, teach us tolerance, aggravate us, anger us, enflame us. Books make us feel.

Special Needs in Strange Worlds, my column on SF Signal highlighting the importance of disabilities in the genre, has just gone to prove to me how important it is for everyone to have a voice, and a spot at the genre table. In so many ways, my column has turned out to be the highlight of my time in the genre. I get to talk to giants each week. I get email from people who humble and profoundly touch me, from the blind woman who uses computer software to keep up with my column, to the gentleman who spends so much time and effort advocating for the disabled and has taught me so much.

The world is full of magnificent people, and I’m beyond fortunate that I get to interact with some of them.

On the other hand, it breaks my heart to realize that in so many ways, the disabled are still a vastly overlooked part of the genre community, with hardly any visibility, and very few people actively working to get disabled voices heard. In matters of diversity in the genre, very rarely do the disabled get mentioned.

There is hope, however. Some authors have been more than willing to openly talk about their own depression, disabilities, or their efforts writing realistic and honest characters that face complicated emotional, physical, and/or mental struggles, and so much more. It’s a small light on a topic that deserves so much more than I’ll ever be able to do for it, but it’s something. The willingness for authors to open up about these sensitive topics has released a flood of readers and other authors who understand, sympathize, and empathize. The conversation is starting. It’s slow, but steady, and largely happening due to the bravery of authors who are willing to open up to the internet about personal matters.

And people are listening.

A few weeks ago I got to be part of my (very first) convention panel, called Disabilities in Genre Fiction. I wasn’t expecting much of a turnout (I have an inferiority complex), and was absolutely astounded when I saw that every seat in the room was full. The panel was one of the most moving experiences I’ve ever had. It was wonderful to be able to actually talk about the issues and people I have been introduced to in my time working with the special needs community.

It was even more touching to hear the stories that so many shared, from the woman whose daughter has cerebral palsy, to the blind man who talked to me after about how hard it is for him to find books that are accessible to his needs, and the gentleman who came up to me with tears in his eyes, clasped my hands, and said, “don’t ever stop.” It was profoundly moving to realize that this was a room full of strangers all coming together to support something that means so very much to me.

It gave me real, profound hope that the disabled, while currently rather overlooked in the genre community, won’t always remain that way. There are giants all around us, inspirational individuals who are some of the strongest people I have ever met. These individuals show what strength of heart really is, and have taught me how to not just love the books I read, but appreciate the lessons and diversity that can be found in them.

Books aren’t just words on pages. They are lives, lessons, mysteries and passions unfolding before us.

My brother, Rob, told me years ago, “I wish people would realize that someone like me can be a hero, too.” That quote is the single reason why I started my column, and that’s a sentiment I will never forget. Heroes are all around us, often silent, lost in the margins—individuals with souls that shine with fire and willpowers of steel. These are the people who deserve to be in the books we read, and the books we write. They deserve to be part of our diversity discussions, and our fight for equality in the genre.

Sarah Chorn has been a compulsive reader her whole life. She’s a freelance writer and editor, a semi-pro nature photographer, world traveler, three-time cancer survivor, and mom to one rambunctious toddler. In her ideal world, she’d do nothing but drink lots of tea and read from a never ending pile of speculative fiction books.

You can find her on SF Signal for her weekly column Special Needs in Strange Worlds, or say hi on Twitter, Facebook, or her website Bookworm Blues.