Lionel Shriver’s Speech on Cultural Appropriation

Today, The Guardian followed up with the full speech from American author and journalist Lionel Shriver.

Shriver begins her speech by describing herself as an iconoclast, and claiming:

“Taken to their logical conclusion, ideologies recently come into vogue challenge our right to write fiction at all. Meanwhile, the kind of fiction we are ‘allowed’ to write is in danger of becoming so hedged, so circumscribed, so tippy-toe, that we’d indeed be better off not writing the anodyne drivel to begin with.”

Look, if you’re going to claim you’re not allowed to write a certain type of fiction, you need to back that up. Instead, Shriver presents the example of a party at Bowdoin College, wherein hosts were punished for passing out sombreros at a tequila-themed party. You can read more about that incident and form your own opinions. It’s interesting to note that this wasn’t an isolated incident at the school. “Last fall the school’s sailing team hosted a ‘gangster’ party where attendees were encouraged to wear stereotypical black clothing and accessories,” and “In the fall of 2014, Bowdoin’s lacrosse team held what was billed as a ‘Cracksgiving’ party that featured students wearing Native American garb.”

ETA: As pointed out by Sarah on Facebook, Bowdoin also has a hard liquor ban, so the sombreros were not the only problem/violation at the party in question.

Shriver goes on about sombreros and Mexican restaurants, and ends on a familiar refrain:

“For my part, as a German-American on both sides, I’m more than happy for anyone who doesn’t share my genetic pedigree to don a Tyrolean hat, pull on some leiderhosen, pour themselves a weisbier, and belt out the Hoffbrauhaus Song.”

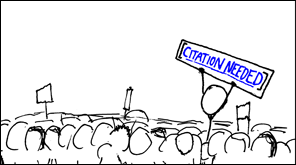

It’s practically a BINGO square in conversations about racism and cultural appropriation. You can’t talk about Native American sports mascots, for example, without white people popping up to say they’re Irish and don’t object to Notre Dame’s “Fighting Irish” mascot, so why do those “oversensitive” Native American’s object to the “Redskins”? Could it be that the situation faced by Native Americans today isn’t the same as that faced by Irish Americans? Likewise, life in this country for someone of Mexican descent is very different from that of someone like Shriver.

But what does all of this have to do with writing and the freedom to write fiction? Shriver continues:

“The moral of the sombrero scandals is clear: you’re not supposed to try on other people’s hats. Yet that’s what we’re paid to do, isn’t it? Step into other people’s shoes, and try on their hats.

In the latest ethos, which has spun well beyond college campuses in short order, any tradition, any experience, any costume, any way of doing and saying things, that is associated with a minority or disadvantaged group is ring-fenced: look-but-don’t-touch. Those who embrace a vast range of ‘identities’ – ethnicities, nationalities, races, sexual and gender categories, classes of economic under-privilege and disability – are now encouraged to be possessive of their experience and to regard other peoples’ attempts to participate in their lives and traditions, either actively or imaginatively, as a form of theft.”

Shriver’s phrasing is fascinating. “Those who embrace a vast range of ‘identities’ … are now encouraged to be possessive of their experience…” Shriver is a professional writer, so I assume her use of passive voice is deliberate. Reading her description, it’s like she sees these people from marginalized groups as puppets being manipulated into building a fence around their experiences and traditions.

Encouraged and manipulated by whom, I wonder. Shriver never says. But it’s a telling bit of wordplay, one that strips marginalized groups of agency.

Shriver goes on to give examples of books in which authors wrote about characters and groups that weren’t like them, which also gives her the chance to drop this bit of grossness:

“…Having his skin darkened – Michael Jackson in reverse – Griffin found out what it was like to live as a black man in the segregated American South.”

A white person having their skin darkened is “Michael Jackson in reverse”?

- Google the word vitiligo.

- Thanks, I guess, for demonstrating the failure mode of clever.

Shriver continues:

“However are we fiction writers to seek ‘permission’ to use a character from another race or culture, or to employ the vernacular of a group to which we don’t belong? Do we set up a stand on the corner and approach passers-by with a clipboard, getting signatures that grant limited rights to employ an Indonesian character in Chapter Twelve, the way political volunteers get a candidate on the ballot?”

It must be so much easier to argue when you just make crap up. Nobody is saying Shriver is never allowed to use an Indonesian character in chapter twelve. No one is saying she’s not allowed to write about characters from other cultures and groups. The Fiction Police are not going to kick down her door, seize her computer, and lock her up in prison for 20 years on Aggravated Cultural Appropriation in the Second Degree.

But wait, Shriver has examples! They’re not about writing, but still…

“So far, the majority of these farcical cases of ‘appropriation’ have concentrated on fashion, dance, and music: At the American Music Awards 2013, Katy Perry got it in the neck for dressing like a geisha. According to the Arab-American writer Randa Jarrar, for someone like me to practice belly dancing is ‘white appropriation of Eastern dance,’ while according to the Daily Beast Iggy Azalea committed ‘cultural crimes’ by imitating African rap and speaking in a ‘blaccent’.”

This is why Katy Perry is no longer allowed to make music. This is why all white belly dancers were arrested in the Great White Naval Purge of 2015. This is why Iggy Azalea is legally required to wear a gag when in public.

Except, of course, none of that happened. What did happen is people expressed opinions. They said they were offended. They might even have (gasp) gotten angry.

Maybe Shriver is one of those “special snowflakes” we’ve been hearing about recently. It’s not that she as a writer isn’t allowed to write about other groups. It’s that she wants to be able to do so without anyone complaining. Without any pushback if she screws up. Without people getting angry. Without anyone daring to write negative reviews about her work, like the one she talked about in her speech:

“Behold, the reviewer in the Washington Post, who groundlessly accused [my] book of being ‘racist’ because it doesn’t toe a strict Democratic Party line in its political outlook, described the scene thus: ‘The Mandibles are white. Luella, the single African American in the family, arrives in Brooklyn incontinent and demented. She needs to be physically restrained. As their fortunes become ever more dire and the family assembles for a perilous trek through the streets of lawless New York, she’s held at the end of a leash. If The Mandibles is ever made into a film, my suggestion is that this image not be employed for the movie poster.'”

Behold, Shriver’s takeaway from this review: “Your author, by implication, yearns to bring back slavery.”

Maybe she simply doesn’t get it.

Strike that. I think we can say pretty definitively that she doesn’t get it. Nor do I suspect she wants to.

Turning to another example, J. K. Rowling has received a lot of criticism lately for her portrayal of Native Americans in the history and backstory of Fantastic Beasts and Where to Find Them. This criticism is not because she dared to refer to Native characters and history in the story. It’s because she did so badly. Because she took sacred beliefs she didn’t understand, and played with them — stretching and distorting and changing and basically pissing all over beliefs people have fought and died to preserve. Beliefs white people have spent centuries trying to eradicate. Rowling’s distortions and portrayal? They’re one more piece of that attempted eradication.

Does this mean Rowling’s not allowed to publish her book? Don’t be absurd. Rowling could write 200 pages about Hagrid’s belly button lint and publishers would line up to publish it. She’s allowed to write and publish it.

And others are allowed to criticize, to point out the harm she’s doing, and to believe she was wrong to write and publish the story the way she did.

Back to Shriver:

“I confess that this climate of scrutiny has got under my skin. When I was first starting out as a novelist, I didn’t hesitate to write black characters, for example, or to avail myself of black dialects, for which, having grown up in the American South, I had a pretty good ear. I am now much more anxious about depicting characters of different races, and accents make me nervous.”

Shriver is now a bit more anxious about how she depicts characters of other races. Somehow, I’m having trouble seeing this as a bad thing. Knowing people will be scrutinizing our writing pushes us to do better. (Okay, sometimes it leads to defensiveness and bizarre accusations that reviewers think you want to bring back slavery, but we can hope for the best, right?)

As a writer, I do have the freedom to write whatever I want. But to my mind, with great freedom comes great responsibility. I have an obligation to get it right, to the best of my ability. To recognize the power of stories. To understand that publishing is not an equal playing field, any more than the world as a whole. To listen. To recognize that there are some stories I’m not the best person, or the right person, to tell.

There’s so much more to say about all this, but we’re already well past tl;dr length. For those who want to better understand the conversation around writing, cultural appropriation, and so on, I recommend the following resources:

- Should White People Write About People of Color? by Malinda Lo

- Appropriate Cultural Appropriation, by Nisi Shawl

- The Writing the Other website.

- Cultural Appropriation, by Aliette de Bodard

- On the topic of cultural appropriation in fantasy, what IS the line…? from the MedievalPOC Tumblr

- Diversity in Fantasy Mine, by Cindy Pon

Michael Nichols

September 13, 2016 @ 7:16 pm

Freedom of Art (like speech) does not mean freedom from consequences. Like you said they can write what they like but people don’t have to buy or praise it.

Ken Marable

September 13, 2016 @ 7:33 pm

Special snowflake is right. Wow.

Plus, for professional writer with enough notoriety to be asked to give the keynote, that was some really poorly thought out, just plain ol’ bad writing.

AJ

September 13, 2016 @ 7:40 pm

I really don’t understand why it is so hard for Shriver, a supposedly experienced author, to actually do her homework. She rattles on about her ‘research’ but it sounds suspiciously like research within her comfort zone. Does she not talk to the people she wants to include in her books? (in the case of the book based on her dead brother, no, she just appropriated his story without asking his feelings on the matter before he passed, therefore the story was all about HER feels around obesity) Does she not get the people she’s writing about to beta read and offer critique on how to better the work? Basic writer etiquette!

Peter S. Hoyt

September 13, 2016 @ 7:49 pm

Sorry, but she is absolutely 100% correct.

Ken Marable

September 13, 2016 @ 7:52 pm

She is apparently just really, really clueless. Like in the NY Times article about the speech (http://www.nytimes.com/2016/09/13/books/lionel-shriver-cultural-appropriation-brisbane-writers-festival.html), apparently someone yelled at her afterwards about coming to Australia to insult their minorities.

Her response? The person had no idea what they were talking about because she didn’t specifically mention any Australian minorities.

*facepalm*

At least props to the festival admins, who when realizing her speech wasn’t going to be about “community and belonging” as she promised, disavowed her remarks and immediately set up additional counter-programming by minority authors.

Jim C. Hines

September 13, 2016 @ 7:54 pm

Sorry (not sorry), but she’s not.

Lee

September 13, 2016 @ 8:51 pm

Gee, I just don’t understand why she’s so sensitive about this sort of thing. If she’s that thin-skinned, then maybe she should consider another career. Fielding criticism is part and parcel of being a writer, after all.

Emily

September 13, 2016 @ 9:10 pm

I saw the subject of the post and thought “oh no! I love that guy’s voice!” and then realized that, no, it isn’t Lionel Shriver whose voice I love, it Liev Schriber–who narrates the NHL series about the Winter Classic. *whew* I’m glad he’s fine.

I read her book about her obese brother–or based on it, or whatever. It was rough. Though, to be fair, when I was done I was absolutely unsurprised that a skinny chick had written it–she was totally writing from her own point of view. There’s nothing wrong with writing about how much your dead brother’s fatness made your life so awful, I suppose, but it was pretty narrow in scope.

I read the piece about why the writer walked out of the speech, and now, with this one, and what I’ve read from her, I’m sure she just doesn’t get it. Which is okay–lots of people don’t get things–but she doesn’t WANT to get it, which is not okay.

Venita Munir

September 13, 2016 @ 9:22 pm

I have a similar opinion to you. Shriver may have valid points about ‘political correctness’ gone mad in SOME instances, but the real issue is offence. If she is blind to her own offensive behaviour, it is not going to be easy to ever reason with her or others of the same ideology. I also published an opinion about this issue at: https://venusianmoon.com/2016/09/12/a-question-of-whos-taken-offence/

Jayle Enn

September 13, 2016 @ 9:57 pm

If there weren’t evidence that a grown woman wrote that speech, I would have assumed it was something from the pen of a frustrated teen who’d just been introduced to Jonathan Swift and Harrison Bergeron. The myopic perspective and half-assed structure is just about boilerplate.

Sally

September 14, 2016 @ 12:54 am

Aw, she got her special snowflake fee-fees hurt. Can we get her a rich white lady safe space to recover from this trauma?

Besides being clueless, she seems to not understand the space-time continuum, since “Black Like Me” was published before Michael Jackson was born, so, um? Nor the meaning of common English words, what with her scare quotes around “identities”? Like, people weren’t black or gay or disabled before recent times?

And what stupid frat parties have to do with the publication of fiction is also beyond the understanding of most people.

Thinking you should be able to say whatever you want without consequences is ALL THE BINGO on white supremacy.

If this is an example of her writing, I’m not impressed with her talent or maturity.

rhethoricandlogic

September 14, 2016 @ 4:17 am

Sally,

I think your attitude is counterproductive. It’s exactly such disparaging remarks, that make a rational discussion so difficult.

Mikki Kendall

September 14, 2016 @ 7:05 am

There is a phenomenon called tone policing that hinges on the idea that everyone has to be nice in refuting bigotry. That sweetly, softly discussing the harm done is somehow better. No one ever ended oppressive behavior by saying please. And I would hope that white people aren’t so fragile they cannot stand to see anger aimed at other people. Well, other white people. No sign tone policing shows up when bigots are talking to or about people of color.

Mikki Kendall

September 14, 2016 @ 7:08 am

It really does seem to be the idea of criticism that she finds so upsetting. Yet, when she decides to put a Black woman on a leash you would think someone might have told her it would end in just that.

Gillian Polack

September 14, 2016 @ 7:15 am

Shriver said something that I’ve heard regularly. A small but vocal minority of writers really do believe that all stories open to retelling and interpretation by writers (which is the core claim that Shriver makes). It’s common enough in Australia that the organisers of Conflux decided on a program item on writing about cultures other than one’s own even before the Shriver talk happened.

Craig Laurance Gidney

September 14, 2016 @ 10:26 am

Newsflash: POC/LGBT/Disabled/Non-neurotypical folks read fiction, too.

Here’s what I think is happening. Shriver (apparently) writes transgressive fiction (By the way, I love(good) transgressive fiction!). That kind of fiction frequently gets interpreted in certain (not always flattering) ways. So she’s disgusted that people from marginalized notice that her marginalized characters are often plot devices rather than real people.

As a writer, you have a right to use characters as plot devices. It’s one of the authorial tricks of the trade. (It’s a hard trick to do, because the line between living metaphor and lazy writing is pretty fine, and readers’ mileage may vary with that particular trick). Readers, however, also have a right to react it as well.

It’s all about the criticism and her fragility.

Takeaways:

1.When you write transgressive/discomforting fiction, you open yourself up to criticism.

2.You’re not just writing for a homogenous audience.

Heckler's Veto

September 14, 2016 @ 11:54 am

“Rowling’s distortions and portrayal? They’re one more piece of that attempted eradication.”

Oh for heaven’s sake. There are people actually attempting to eradicate minority populations right now, but some English waif is “eradicating” history by writing some lazily research fiction. Ooookay.

Maybe we can tone down the hyperbolic virtue signaling, hm? You’re progressive. You support native peoples. We get it.

Jim C. Hines

September 14, 2016 @ 11:58 am

Paraphrase: “I don’t understand how stories can contribute to the erasure of culture and history, so I’ll just throw mockery instead.”

Yvonne Jocks

September 14, 2016 @ 3:45 pm

Not just absolutely, but 100 percent correct? Do you realize that few if any humans in this universe are or ever have been absolutely, 100 percent correct about anything? I am not. But I am pretty darn sure that–while Shriver brought up an interesting area to explore, about the importance and challenges of including diverse character types–she did so poorly. As a self-stated “iconoclast,” perhaps she wanted the controversy.

Stephen Watkins

September 14, 2016 @ 5:15 pm

My intent in the following comment is to be respectful here, both because (a) I have enormous respect for you (Mr. Hines) as an author and blogger and because (b) I want to count myself among the progressive allies in these circumstances, but I must also check my white-male privilege, and recognize that my own experiences will inevitably cloud my judgment, but that this is no excuse for behaving poorly.

I empathize with the anger of under-represented minorities and groups – especially struggling/aspiring authors from these groups – when they find their culture, traditions, and experiences appropriated and handled poorly by members of the dominant race/gender/culture. I like being able to hear these fascinating stories and myths from those people who are closest to them, and can give us those stories with the nuance, depth, and richness they deserve.

But, conversely, claiming that J.K. Rowling is participating in an “attempted eradication” of Native American culture and beliefs just smacks of hyperbole. That’s giving her a malicious intent and motive that I doubt actually exists. I am reminded of the aphorism called Hanlon’s razor: Never attribute to malice that which can be explained by stupidity. Or, in this case, ignorance and a failure to adequately research the topic. There’s all kinds of aspects of white privilege that we could unpack in why this happened, but turning Rowling into a caricature of an Andrew Jacksonian villain seems a bridge too far.

While Shriver definitely sounds clueless, and proudly so, I think there is a real fear among some white authors with regards to the subject of “Writing the Other”. (Note: those are not intended to be scare-quotes, but rather I am attempting to offset the phrase as a term-of-art, as it is frequently used in these discussions.) The need for writers to be thick-skinned notwithstanding, just as a matter of course, when a failure occurs in attempting to write the other results in criticism that sounds like the author is being accused of perpetrating a genocide, that’s pretty hurtful. I’m aware that this will read like tone-policing, and I respect that often the anger and outrage is justified. Certainly, in Shriver’s case, by all accounts that outrage is definitely justified. In Rowling’s case? I’m less inclined to agree. (Again, recognizing that’s possibly, maybe even probably my white privilege speaking.)

As a matter of disclosure: besides being a white male, I’m also an aspiring author. Hell, I expect I’ll always be “aspiring” and never professionally published author, though I hope never to give up the dream. (I’m creeping up on middle-aged, and some part of me keeps saying if I haven’t published my first book before my 40s then I’ll never be published at all.) And I have stories I want to tell that have characters, even main characters, that are not white males. My intention, when writing those stories and those characters, is to treat them as fully-realized, multi-dimensional people with history and internal lives and all the things that make them interesting and engaging. But my experience is limited, and I know I will sometimes stumble, sometimes fail. And it’s hard to know where the boundaries lie. I’ve tried to read widely on the subject of writing the other, and I’ve certainly sometimes been given the sense that it’s never permissible, that it’s always a hateful act to write stories that reference characters and cultures not the author’s own. I’ve also seen very sound arguments that not including such characters is the worse failure. I don’t know where the consensus lies (my reading on the subject is not, I know, a complete survey). My personal feeling is that it is worse to try and fail than not to have tried at all.

But if ever my work is published and widely available, I hope not to be accused of genocide when those failures are faced by the public. Ignorant, hackneyed, trite, cliched. I think I can take that, though I’d hope I was better than that, too. But to be viewed as a hateful person… I don’t know what to say to that.

Is there a consensus on this topic?

I know from my study of the subject that it often comes down to doing your research. As an aspiring author of secondary world fantasy, though, I’m not sure I even know how one goes about doing such research. Any thoughts you or other visitors to your blog have on the topic are very much appreciated.

Jim C. Hines

September 14, 2016 @ 5:41 pm

Stephen,

Well, this is the internet, after all. I don’t think there’s ever been a consensus on any topic.

I think I understand what you’re saying and how you’re reading that part of my post. I agree with you in that I don’t believe there’s any malicious intent or malice on Rowling’s part. On the contrary, most of what I’ve seen of her actions has been generous and compassionate.

Let me spell out my thinking on this. My country has a long history of trying to wipe out Native Americans. There’s the blatant wars, bounties for Native scalps, and the ongoing slaughter. Later on, you get institutionalized attempts to erase and wipe out Native cultures and beliefs. Children being taken from families. Forcing Native Americans into white dress, white schools. Punishing anyone who dared to speak their native language instead of English.

I grew up with toy cowboys and indians and shows that taught me “Indians” were a thing of the past, basically wiped out.

We’re *still* teaching these lessons. We’re still erasing the indigenous people of this country from our history, from our politics, from our stories, and so on. We caricaturize them. We ignore problems like this: http://thefreethoughtproject.com/navajo-water-supply-horrific-flint-cares-native-american/

We’ve been trying to eradicate Native Americans for centuries.

And one piece of that has been to punish people for their beliefs. For their history and culture. To turn it into stereotype. To erase people’s religious practices and traditions.

The way Rowling took sacred beliefs that she didn’t understand and didn’t research and twisted them about? It wasn’t fitting true history with her fantasy world. It was presenting her own ignorance as history and fitting *that* with her fantasy world. It’s one more example of erasure, of treating real people as if they don’t exist except as props.

My initial thought was to write that Rowling was part of the ongoing eradication of Native American history and beliefs. The biggest or most horrible or most malicious part? Nope. But her actions are a part of that ongoing history.

The thing is, that eradication failed. We didn’t erase Native American people. We haven’t wiped them out. We’ve tried for centuries, but they’re still here. So it felt more accurate to label it attempted eradication, so as to avoid suggesting it was successful.

“But if ever my work is published and widely available, I hope not to be accused of genocide when those failures are faced by the public.”

I never accused J. K. Rowling of genocide. I do accuse her of being part of this centuries-old movement to erase Native Americans. I don’t think she’s a hateful person. I do think she screwed up, and she’s hurting real people. I don’t think she’s a villainous caricature. I do think we tend to minimize or ignore just how much damage we’ve done to these populations over the centuries, and how much damage we continue to do.

Kate Kulig

September 14, 2016 @ 6:06 pm

Wow, so much to critique about that speech, starting with using the word iconoclast completely wrong.

I think your analysis is spot on and I thank you for the links. Of late, I’ve been reviewing my previous novels and realizing where I could do a lot better with the POC characters. All this helps.

gwangung

September 14, 2016 @ 6:52 pm

Folks have a right to write whatever they want.

But other folks have the right to criticize what’s written. And if what’s written is badly done, then I think the criticism is warranted. If what’s written is actually well done, then a criticism will fail, because it won’t find purchase.

A lot of cauterwauling about political correctness is cover for the inner realization that the writer really isn’t good enough to write the Other well.

Gabriel F.

September 14, 2016 @ 7:58 pm

Entitled white lady bitches about being called on her shit. Film at 11 🙁

Thomas Hewlett

September 14, 2016 @ 8:14 pm

Okay. But why? I think it’s great that her speech is sparking so much discussion. So I’m curious to hear more from another opinion.

Stephen Watkins

September 14, 2016 @ 8:15 pm

I guess my problem is with the equating of poor or lazy research with attempting eradication. Those words read like “genocide” to me. There’s no question that our history had a long and very very ugly period in which actual attempted genocide was an ongoing thing. There’s no question that our modern policy at s national level toward native peoples is more than a little lacking . There’s no question that our history includes ongoing attempts to erase the living memory of native traditions and culture (vis-a-vis religious conversions, adoption of native children by non-indigenous, usually white families, etc.) These are all real problems.

Poor and lazy research is a real problem too. But I just have trouble adding it to the same list of evils. It doesn’t logically feel like part and parcel with the actual evil history of eradication and genocide. The only linkage is in the white privilege that also plays a role in those other systemic crimes.

The phrase “attempted eradication” connotes intent in the same way “attempted murder” does. I don’t see that motive and intent. Ignorance and white privilege are problems of inaction but while they may result in harm done they don’t necessarily arise from an intent to do such harm.

Should Rowling be held to a higher standard, being the famous and wealthy author she is? Yes. Absolutely. But this use of language looks like something else. It looks like contempt.

Shriver may deserve that contempt, the way she has shown contempt for the idea of cultural sensitivity. It doesn’t feel fair to paint Rowling with quite the same brush. I guess that’s where I’m having a problem.

When actual violence is being done to Native Americans right now, practically in real time, implying that a popular author is actively participating in violence against the same by dint of her poor research sets a critical precedent. And that atmosphere has an impact on authors who intend to show respect to native cultures but will now fear to write anything portraying native people because they fear being mislabeled an enemy of those people.

I can’t see into Rowling’s heart. I don’t her intent but obviously I suspect her only of ignorance and nothing more sinister. It is an ignorance, I am ashamed to say, I largely share in spite of my own supposed native roots. (It seems almost axiomatic that any given white guy opining about Native Americans claims to have some Native blood. I’m told our family does, on my mother’s side, but I’ve never done the genealogy work to prove it.)

I know the fear of being accused of some evil intent exists because, as a white male aspiring author who lacks the shields of fame and wealth, I have these fears. I doubt I am alone. But, as stated in my first comment, it is my desire and intent to be respectful and accepted as an ally. Were I to be published, I wouldn’t my audience to look substantially like that of some sad sack author that’d been expelled from SFWA.

Stephen Watkins

September 14, 2016 @ 8:21 pm

Wouldn’t want my audience to look like, etc.

(I’d rather be appreciated by the same sorts of folks who appreciate the works of NK Jemisin, Scalzi, and too many other talented and progressive and respected authors to thoroughly list them all.)

Writing across cultural boundaries in the contemporary era | Angela Savage

September 14, 2016 @ 9:56 pm

[…] I see it as a privilege. And with privilege comes responsibility. As novelist Jim C Hines put it in his excellent rejoinder to Shriver’s […]

KatG

September 15, 2016 @ 12:35 am

It’s not about Rowling’s intent. It’s about the effect of her actions, witting or unwitting. If I hit a child with my car because I drove poorly, and it was an accident that I didn’t mean to do, the child is still harmed. Likewise, poorly thought out portrayals of Native Americans, that treat them as all one people and play into bigoted stereotypes of them as inferior and exotic Others who can be used as white people feel like for the profit of white people, harms Native Americans’ ability to get their equal civil rights and have their own, real voices heard, especially when coming from the most famous author on the planet. She caused harm. And therefore people criticize her not to harm her but to raise awareness — for both Rowling and for other white writers and for other non-Native Americans in general — that this sort of portrayal affects Native American rights in real life, that it is harmful because it does not treat them or portray them as equal human beings, with any real respect. They criticize so that writers in the future, including hopefully Rowling, will do it better with less unintentional bigotry. They criticize it to point out that Native Americans are actually being blocked and prevented from discrimination from telling their own stories and selling their own art by bigoted stereotyped views of them. It is part of making the world better and more equal — something that Rowling is fully in favor of. And more to the point, it’s free speech. Saying that they should shut up about routinely bigoted portrayals of their culture and history is just everyday intimidation. Rowling did not earn the respect of the people whose culture she was using in what they feel is a harmful and thoughtless manner for them in real life. They thought it was bad writing, and that part of it was, I agree.

KatG

September 15, 2016 @ 1:38 am

Fun stuff with the idea that civil rights are a “fad” that is “in vogue.” This seems to be the big current rhetorical device — civil rights discussions, criticism and protests are just fashionable, you see. Nothing to do with long standing and actual injustice, discrimination, violence, etc. Just hyperbole by inconvenient pills, blah, blah, blah. No criticism on that front is ever allowed; how dare readers have opinions about writing.

There is a fair amount of criticism coming at the Brisbane festival folk because Shriver has given this type of speech before so it’s claimed that they knew she would do it there and then pretended to be shocked by it to deny responsibility for giving her the platform for it. I don’t know about that in this case, but that is often a typical situation.

Stephen Watkins

September 15, 2016 @ 9:38 am

See, it’s not the criticism that bothers me. It’s how it’s framed. The way you wrote it, I generally agree. Rowling set a bad example, and we all owe it to the rest of humanity – Native Americans, African Americans, and every other underrepresented voice – to do better. I’m on board with that. However, criticizing her (Rowling, or anybody else who made a mistake) in such a way as to imply she is complicit in genocide, I kind of object to that.

That said, one way in which I disagree with you is that I’ve always believed that intent still matters, even if harm is done. Good intentions don’t erase the harm nor the need to make amends. But they should ameliorate the punishment, as it were. Someone with good intentions that does harm is a good person who screwed up. This, as opposed to say some poor-excuse for a human being SFWA-reject as a counter-example. One of these two is actually advocating for genocide and putting it into their work. One was ignorant and screwed up. I feel like it’s not the same.

On the subject of the original post’s author in question, for example: Ms. Shriver seems to deserve the very negative reaction she is getting, based on the nasty content of her speech. There’s definitely something ugly lurking there.

Avilyn

September 15, 2016 @ 11:06 am

Poor and lazy research is a real problem too. But I just have trouble adding it to the same list of evils. It doesn’t logically feel like part and parcel with the actual evil history of eradication and genocide.

Here’s the thing though – many Native Americans felt as though it was a slap in the face, horrible erasure of their varied cultures. *You* might not have felt like it was on level with the history of erasure and genocide, but to many of them (at least the ones I listened to who spoke out about it), *did* feel that way. This is not to say that there aren’t other injustices ongoing (Standing Rock for one, as you note), or that those other things aren’t important, but that it’s something IN ADDITION TO those other issues that contributes to their erasure.

Stephen Watkins

September 15, 2016 @ 11:18 am

Fair enough. I’m a white guy on the internet, so I know my opinion doesn’t count for much in this discussion, and that’s perhaps as it should be. Be that as it may, I never actually saw outrage from Native Americans so much as outrage on behalf of Native Americans from other white people. Is that mainly because of my narrow reading interests? (I mainly follow blogs of authors I already read, and a few others, but it’s impossible to keep up with everything. I pretty much don’t follow Twitter at all… keeping up with just Twitter is also impossible for me.)

I’ll step back from the conversation then. I can’t speak for what should or shouldn’t offend Native Americans or any other group; not my place. I can only say that I find it hurtful to claim that an author who made a mistake is participating in “eradication”, when I know I’m very fallible and prone to making similar mistakes, even if I’m trying harder to learn and understand as best I can.

Thank you all for your responses.

Jim C. Hines

September 15, 2016 @ 12:44 pm

Stephen – on the distinction between outrage from vs. outrage on behalf of…

http://news.nationalgeographic.com/2016/03/160311-history-of-magic-in-north-america-jk-rowling-native-american-stereotypes/

http://www.dailydot.com/irl/native-americans-upset-with-jk-rowling-elizabeth-warren/

http://indiancountrytodaymedianetwork.com/2016/03/09/jk-rowling-native-american-wizards-called-skin-walkers-pottermore-website-163694

http://nativeappropriations.com/2016/03/magic-in-north-america-the-harry-potter-franchise-veers-too-close-to-home.html

https://www.buzzfeed.com/susancheng/jk-rowling-native-americans

There’s no perfect consensus on there. Native Americans aren’t a monolith any more than any other group. But hopefully some of these links will be helpful.

One of those ‘issue’ pieces which stupid writers post on their blogs to ruin their reputation in public – ANDREW LEON HUDSON

September 15, 2016 @ 2:27 pm

[…] since this post, I’ve also read this piece by Jim Chines, which goes a long way to underscoring just how misjudged Lionel […]

Stephen Watkins

September 15, 2016 @ 3:01 pm

It is helpful. And I am forced to correct my statement that I’d only read outrage on behalf of Natives. In fact, I had read the Adrienne Keene piece at the time, but my memory elided the fact that she identifies as Native.

So, on that account, I stand corrected. Rereading that, it struck me that for many who identify as Native American, they could easily pass as white if they chose: many have Anglo-sounding names, and many don’t have any identifying physical characteristics that look stereotypically Native when you see them. I don’t have a point to make about that, but I just thought it an interesting observation.

KatG

September 15, 2016 @ 4:02 pm

You’re policing their speech. And yes, it does contribute to genocide because we are still committing genocide against Native Americans and justifying it with the same bigoted crap and portrayals of Native Americans while blocking them from the market with their voices. Inequality causes genocide all the time — that’s part of what it’s for. Culture does in fact kill people. Pretending that what ruling groups do in their culture, arts and entertainment has no real life effect on repressed groups then helps keep the bigotry and its effects, deadly to wasteful, in place. So yeah, Rowling contributed to the marginalization and discrimination and deaths that white people still inflict on Native Americans. We pretty much all do until we stop doing it.

Here’s how cultural appropriation works: The people in Culture A use violent force, genocide, rape, enslavement, imprisonment, and outright theft on people in Culture B to control them, exploit them and take their stuff. They justify it by portraying people in Group/Culture B as inferior to Culture A and less human — less smart, more lazy, incompetent, etc., that they are doing Culture B a favor by killing them, etc. Over time, Culture A may be a little less violent towards Culture B because of the efforts of Culture B for social justice, but they still block Culture B and control them and cause their deaths, still often by violent force or starving them, etc. As part of that, they declare Culture B to also be sexy, edgy and exotically different from the superior normal culture, and they take that culture and use it for themselves to present Culture B stuff as for Culture A’s pleasure and entertainment and betterment, and make tons of money off of selling that exotic culture, while blocking as much as they can the people from Culture B from being able to also sell, and condemning people in Culture B from having the very same culture they are using for their own profit.

So black people are condemned for having cornrows in the workplace, as inappropriate and too edgy gangster to make white people comfortable. At the same time white salons make a fortune selling cornrows for whites, which is considered perfectly fine. Selena Gomez dances around in Indian clothing with Bolly dancers for a song, making herself a profit and parading an exotic stereotype image of Indian culture, while Indian singers are shut out of the same markets and subject to violence for being inferior Indians with a weird exotic culture. Rowling used Native American culture — and religion — badly and bigotedly for her own writing and profit. Meanwhile Native American writers can barely get published, are told to not write about their cultures, or to only write about their cultures, that they are niche, that they should assimilate more into white culture, etc. Everybody loves to put on the feather headdress and talk about their spirit animals because we see Native Americans as toys and who cares if we portray their culture accurately or just as a crude stereotype. At the same time, because of that view, nobody wants to hire Native Americans, give them decent schooling, provide reservations with electricity, give them decent healthcare, listen to them, or care about violence and murder aimed at them by the police or anyone else. They definitely don’t want to change the name of a football team that means joyous slaughtering of Native Americans.

You can kill off a people in other ways than just firing a gun at them. That’s fastest, but it means you can’t exploit them slowly, hold them down as inferior to you, and take anything they make and then have them die, most of their culture ignored and erased, secure in the knowledge that you are a great superior person and it’s totally normal and not engineered at all that your kind owns and runs nearly everything.

And that’s cultural appropriation — it’s the slow campaign to keep Culture B in continued poverty, marginalization and early, often violent death, while taking all their best stuff for the profit and fun of Culture A.

So, does Rowling want to shoot Native Americans? No, she does not. Is her half-assed use of their cultures contributing to the process of marginalizing and killing off of Native Americans and their cultures by white society? Yes. And people bring it up to show starkly that it is that serious, society wide. That it is a big deal each time it happens, and causes harm. They do not dress up the demon baby gnawing at people in a pretty tuxedo so that the individual white people feel better. Because when the white people, or the guys or the straights, etc. feel better, they make inequality even worse. They feel more justified that systemic bigotry towards targeted groups is normal and those groups shouldn’t make a big deal and shake up Culture A about its inequality and the consequences for those not considered part of Culture A.

Whether it’s a slight fly-by like Rowlings, or deliberate threat like Beale (who also likes to claim a Native American ancestory,) it all contributes to the same thing — the wiping out, exploitation and marginalization of Native Americans. So it doesn’t get excluded from the conversation.

Here’s a good quote from Scott Woods on this: “The problem is that white people see racism as conscious hate, when racism is bigger than that. Racism is a complex system of social and political levers and pulleys set up generations ago to continue working on the behalf of whites at other people’s expense, whether whites know/like it or not. Racism is an insidious cultural disease. It is so insidious that it doesn’t care if you are a white person who likes black people; it’s still going to find a way to infect how you deal with people who don’t look like you. Yes, racism looks like hate, but hate is just one manifestation. Privilege is another. Access is another. Ignorance is another. Apathy is another. And so on. So while I agree with people who say no one is born racist, it remains a powerful system that we’re immediately born into. It’s like being born into air: you take it in as soon as you breathe. It’s not a cold that you can get over. There is no anti-racist certification class. It’s a set of socioeconomic traps and cultural values that are fired up every time we interact with the world. It is a thing you have to keep scooping out of the boat of your life to keep from drowning in it. I know it’s hard work, but it’s the price you pay for owning everything.”

Sabrina Vourvoulias

September 15, 2016 @ 4:38 pm

Speaking as someone whose extended family and forebears are represented by those tequila-party sombreros …. If Lionel were even a tad self-aware she might acknowledge that the last time a presidential candidate ran on a platform that hinged on raising a wall to keep German “rapists and criminals” out of our country was never and, yes honey, it does make a difference. That whole anyone-can-put-on-lederhosen-and-I’ll-be-happy thing is disingenuous AF. The saddest thing is that is just her warm-up salvo. *smdh*

SunflowerP

September 16, 2016 @ 4:18 am

“But they should ameliorate the punishment, as it were.”

This really stood out for me, and I wonder if it’s part of why you’re struggling with the issue.

Jim’s response to Rowling’s missteps (and to Shriver) isn’t [i]punishment[/i], but [i]rebuttal[/i] – the purpose is to refute the misinformation and ignorance, and take a stand against harmfully false information, not to impose a penalty on either writer. I’m sure it feels pretty shitty to be on the receiving end of such disapprobation (especially when it’s not just one person but what seems like the entire Internet falling on one’s head), but if Rowling, or Shriver, or J. Random Author, parses it as punitive, that’s making it All About Them, rather than about the misinformation they promulgated.

As for ‘good intentions’ – maybe I’ve become excessively cynical over the years, but it seems to me that this is most often used to mean ‘lack of bad intentions’. Trouble is, they’re not synonymous; a lot of the time, the person with a lack of bad intention is a person who doesn’t have formed, conscious, deliberate intentions of any sort, good [i]or[/i] bad. From everything I’ve heard about her, I agree that Rowling did not have malicious intentions – but if she had [i]formed[/i] good intentions, she would have backed them up with a little research (in some cases, it would have taken [i]very[/i] little research – the strongly negative connotations of ‘skinwalker’, f’ex).

Megpie71

September 16, 2016 @ 8:25 am

The whole Iggy Azalea thing is actually a lot more complicated than you’d think. Firstly, as a white person, she’s going to cop it for using rap because rap is historically a black art form – and it doesn’t matter which accent she uses in order to do it, there’s still going to be that element of appropriation in there. However, as an Australian, she gets a certain amount of negative points because she’s using “blaccent” rather than her own Australian accent for a number of reasons.

1) It shows a certain amount of “cultural cringe” – an Australian inferiority complex, where we don’t regard our own culture as being worthwhile or interesting enough to hold its own on the international stage (and this is a problem for both white Australians and Australians of colour). There has actually been a lot of argument within the Australian rap and hip hop scene regarding the use of Australian accents in preference to “blaccent”.

2) There are historical reasons why Indigenous Australians, in particular, prefer to be using their own accent rather than “blaccent” when rapping – and they have to do with the culturally specific reasons why “blackface” (particularly “minstrel” blackface) is extremely culturally uncomfortable here. Basically, the context is this: in the gold rush years of the 1870s, a number of “Negro minstrels” came to Australia as performers, and, performing in blackface, offered up racist jokes which were aimed at the Indigenous population – in effect, creating a hierarchy of “blackness”, with the US Negro at the top, and the Indigenous Australian at the bottom. It still rankles even now, and the after-effects of this process are still present even today.

3) So as a white Australian woman who raps in “blaccent”, Iggy Azalea is basically throwing larger rocks into a bigger minefield of racial issues than, for example, someone like Pink (to use an example of a white[1] woman from the USA who raps).

[1] I don’t know what Pink’s actual racial or ethnic identity is. In the few video clips I’ve seen of her, she comes across, to my Australian eyes, as white – that is, she looks as though she could pass for Anglo-Celtic without too much trouble.

Fraser

September 16, 2016 @ 9:45 am

If I hit a child with my car because I drove poorly, and it was an accident that I didn’t mean to do, the child is still harmed.”

True, but we’ll probably judge you differently than if you ran over the child with the intent to injure her.

Mr. T

September 16, 2016 @ 3:59 pm

I won’t disagree with you that Shriver is an idiot, but I do disagree that the criticisms of iggy azaelia/katy perry/etc is just criticism and no big deal. Iggy Azaelia got a lot of flack for allegedly appropriating african-american culture, and those handful of internet thought pieces (and some haranguing from rapper azaelia banks, who got kicked off twitter for making racist comments to a singer of middle eastern ancestry) have become part of the narrative around her work. And despite the fact that the majority of people seem to regard classifying belly dancing as appropriation as absurd, that too is no doubt becoming part of the narrative. Perry dressed up in an Asian-themed outfit and made some (but not all, and maybe not most) asian-americans upset, and that has followed her. She’s the culturally insensitive privileged white girl who is appropriating asian culture.

This is my issue with a lot of conversation about cultural appropriation on the interwebs. It becomes about branding people as racist, and in our backwards american culture, we all jump over one another for the opportunity to prove we aren’t racist by pointing out someone who is.

and some of what gets categorized as appropriating, as well as some of the theory around appropriation and how not to be appropriative,is up for debate. It’s pretty clear that wearing a headdress or having a mexican taco party are culturally insensitive. It’s much less clear to me that wearing a bindhi, having dreadlocks (or even using the term “dreadlocks”), belly dancing, or interacting with cultures that are not your own are always wrong, or who gets to decide they are or are not wrong. And there isn’t really a great way to respond to being called a racist by someone online. Yes, it’s just criticism, but it is criticizing someone by accusing them of one of the worst things you can be accused of.

Jim C. Hines

September 16, 2016 @ 4:07 pm

“but it is criticizing someone by accusing them of one of the worst things you can be accused of.”

As someone who’s been accused of racism, and someone the Rabid Puppies have taken to routinely accusing of being a pedophile, I disagree with your statement.

I grew up in the U.S., surrounded by racism and sexism and homophobia and other forms of bigotry. How much of a fool would I be to think none of that had rubbed off? That I’d somehow spent 42 years immersed in this without it ever affecting me?

I’ve had people call me out for being racist or sexist or transphobic and so on. In many cases — probably most cases — they were right. It wasn’t intentional on my part, and I don’t think it makes me a Horrible Person. It makes me a human being. We’re all flawed. I like to think I’ve gotten better over the years.

But being told you or something you said or did is racist? It stings. It sucks to be on the receiving end of that criticism. But it’s not the end of the world.

Hell, you can be obscenely racist on national TV and still win the presidential nomination of a major political party…

gwangung

September 16, 2016 @ 5:04 pm

Accusing someone of racism isn’t the worst thing you can be accused up. Prejudice is quite pervasive and there is rarely a person who is entirely free of it. I actually think trying to paint racism as a black, black sin for which there is no forgiveness is actually an attempt to underplay the effects and impact of racism; saying racism is only the KKK-style white sheet/lynching behavior allows other, less blatant, but probably no less damaging behavior to fly under the radar as not being damaging….it gets excused and it gets allowed, instead of being checked.

I will push back against that line of argument because it lets people off the hook. It makes no pressure to change behavior that is damaging (because you’re not lynching anyone); it allows people to slide by without attempting to change their behavior.

Sally

September 16, 2016 @ 11:49 pm

I’m a well-educated, fairly well-off white lady myself who on occasion has had a thing or two published.

I’m calling out one of my own for being clueless and childish.

People like this make me look bad in addition to hurting so many others.

Tone policing sucks — and it’s another square on the bingo card against women, PoC, LGBT, disabled, etc. etc.

Sally

September 16, 2016 @ 11:51 pm

Doesn’t anyone in her life know and care enough to say “You’re gonna get pushback on that?” To warn her that criticism is coming? She’s free to put that in her work, but she should have known it wasn’t going to sit right with others.

Sally

September 16, 2016 @ 11:53 pm

I would like to put “Freedom of speech does not mean freedom from consequences” everywhere until people of all races, creeds, colors, genders, politics, etc. get it.

News & Notes – 9/17/16 – The Bookwyrm’s Hoard

September 17, 2016 @ 12:01 am

[…] Roils a Writers Festival (New York Times) For another take on Shriver’s speech, read Jim C. Hines’s blog post about […]

Sally

September 17, 2016 @ 12:04 am

The child’s operations, broken bones, and pain are exactly the same, though. When the grown-up is limping through life with screws in their leg and wondering how many more pills they can take for the arthritis, they’re aren’t going to think “But it’s not that bad since the person who hit me 40 years ago didn’t MEAN it.”

Rowling also didn’t respond to the criticism, even as little as a non-apology apology. She just ignored it. THAT is on purpose.

KatG

September 17, 2016 @ 12:16 pm

You’d judge me differently if I’m a nice white woman who didn’t mean it than a black woman who would be blamed for driving poorly. If we have a system where one group can be poor thoughtless drivers and frequently injure people in another group (who mostly aren’t allowed cars,) without anyone talking about improving driving training and laws about hitting people with your car — and we do have that system — then the judging differently comes from the bias in favor of the driving group, not from the actual damage being done by people who could change their behavior but chose not to and don’t want to be blamed for it. That’s Shriver’s beef. She doesn’t want any criticism of her driving from the folk she’s hitting. But realistically, authors have no control over readers’ reactions. She’s trying to police her readers because non-whites being less afraid in the English realm to speak up about this stuff is upsetting her upper middle class white existence. And it’s not going to work. They will keep launching this defense of bigotry because they think it benefits them and causing lots of harm to people with their cars, but the people are going to keep criticizing their driving in hopes of reducing both deliberate murder attempts and accidental hits. And also getting to drive cars themselves. 🙂

KatG

September 17, 2016 @ 1:17 pm

No, being accused of racism is not one of the worst things you can be accused of. That’s a common white person fallacy because white people don’t get accused of things that get them killed. Because white people refuse to acknowledge that every day we hold the power to decide whether black people, for instance, get killed, beaten, arrested, etc. in the countries where we rule. We don’t have to be famous to do it; we just have to be standing on the street and say the word. Claiming we can’t be called racist is an attempt to shush criticism about what we are doing and pretending our entire society isn’t racist and enforcing racism. Until you stop the pretense, the racism isn’t going to stop and gets worse.

Which is why the upset at Azalea, Katy Perry, etc. They are white artists who are borrowing the culture/musicianship of black and Asian artists, etc. And they get rewarded for that with sales and awards. Meanwhile black, Asian and Latino artists mostly get shut out, particularly in the U.S. They are told that their culture — the one the white artists are using to great success — is bad, deficient, and they shouldn’t use it. They are told that they are niche, often forced into niche markets, and they face all kinds of discrimination and missed opportunities. They get less promotional support from their record companies, something they’ve worked very hard to change. And they lose out to the white artists on the major music awards on a disproportionate rate. The music industry is heavily racist and biased towards white artists. So when that’s happening and then white artists on top of that borrow repressed cultures for their videos, concerts and songs, there is going to be criticism because it is imperialistic white people stealing stuff to profit off of what non-white artists did first but they get more praise and support for it than the non-white artists.

And what they do borrow tends to be stereotypical bigoted views of that non-white culture — the blaccent, the white people cornrows, the geishas, etc. — things that present non-whites as inferior but exotic Others — props. So the flack at artists like Azalea, who got promoted way more than most black woman rappers very quickly, is part of the larger movement to change bigotry in the music industry and get white artists and their handlers to start taking more responsibility for their own art rather than promote prejudice towards non-whites with their art, while opening up more opportunity for non-white artists, especially when they do art that isn’t white approved culturally.

That’s why there is so much support for Beyonce, because she broke barriers in what was allowed to black women in the American music industry, including awards, which opened the way for a lot of black artists in the last ten years. And the more she uses black culture in her music, the more flack she gets from white people about it, especially because it is successful. She is promoting positive, complex images of black culture and pointing out that injustice and repression is forming part of that culture. Which makes a lot of white people very uncomfortable. They want to shut down the conversation and get Beyonce to stop making art that looks at prejudice and white views of black people, and they want to shut down criticism of white artists who are trying to borrow non-white culture for their acts at the expense of non-white artists. Because it goes places and exposes things that they don’t want to go and see, and requires changes in the behavior of white people, including especially those who would actually prefer to be less bigoted.

The history of American music is one of theft. Elements of country music, and swing, jazz, R&B, rock, pop, rap, hip hop — all mainly taken by white artists doing what black artists were doing, with some borrowing from Latino artists. All while the non-white artists had to go through the back door through the kitchen and fight to change that. In recent years, Asian music has been sampled a lot. Name the number one Asian American singer in America right now. The number one Arab American singer? But we’ve got white artists freely using Asian and Arab cultural stuff and styles, like Perry, to great success.

So instead of constantly trying to defend from all accusations of racism — and we’ve all been there — it really helps when white people start listening to where that accusation is coming from and looking at the historical context and cultural power dynamics of the situation. Because the main reason that racism is still so systemically pervaded in our culture is that white people bigotedly dismiss non-white concerns and claims and obstacles about it. It doesn’t seem to them so bad a thing and the white person being criticized may be nice in other ways, but it’s part of a larger, destructive pattern of oppression. And that doesn’t change unless it gets criticized and pressured to change.

Shriver is trying to claim the pattern isn’t there or if it is, it’s not important. And so she declares her work off limits from criticism in that vein. But the very point of increasing equality is that the criticism isn’t off limits — that non-whites can speak their views and push for change just as much as whites. And a lot of white people aren’t happy about that aspect of equality, largely because they aren’t used to it. They’ve been shielded by a racist system that painted a rosy picture of how nice and trusted they are for them, while placing high and dangerous costs on non-whites speaking up in white-run cultures. As non-white people speak up anyway and punch holes in the shield at great cost — such as the writer who walked out of Shriver’s speech and wrote about why even though it will get her death threats — it’s freaking a lot of white people out. And Shriver is arguing for patching up the shield. It’s not a battle she’ll win unless she gets herself an army and starts slaughtering people — and that only works temporarily.

But for the moment, she gets to give herself a boost with a bunch of other freaked out white people. For bravely standing up for patching the shield against the non-whites who are clearly, for Shriver, because they are non-whites, lying, vicious, overly sensitive, less intelligent beings who have been unfairly exalted (PC culture,) and should instead shut up. She gets to be controversial and daring — to some white people. To most non-white people, she’s standard variety status quo.

KatG

September 18, 2016 @ 1:36 pm

Just FYI, a not bad source for learning more about cultural appropriation and its effects is the website Nerds of Color: https://thenerdsofcolor.org/ While it concentrates its coverage on comics, movies and t.v., those things often also include books and what they look at also applies in part to the fiction publishing industry. The articles there show how what many people accept as normal because we are used to seeing it, contains a lot more skewed cultural landmines and a different perspective for people of color and about the importance of realistic and proportionate representation. It also gives a lot of good info about cool projects you might not have heard much about.

Lionel Shriver and the responsibilities of fiction writers - News blog

September 18, 2016 @ 8:18 pm

[…] are encouraged to think critically about how this shapes their writing. Novelist Jim C Hines argues that engaging in a process of scrutiny actually creates better writers. Privileged writers could also consider how to support and help […]

Fraser

September 18, 2016 @ 8:33 pm

Sally, sure the pain is the same regardless of motive, but the judgment isn’t. That’s why hate crimes are judged differently from regular assault, even if the physical damage is exactly the same.

Kat, I agree that Shriver’s position is quite indefensible.

Sally

September 19, 2016 @ 2:11 am

Are they also shocked there was gambling in Casablanca?

Mr. T

September 19, 2016 @ 8:13 pm

I’m not agreeing with Shriver, or saying that white artists shouldn’t be thoughtful when engaging with artifacts and art from other cultures. But I do think that the basic tenet of cultural appropriation, the idea that culture somehow belongs to anyone, and that engaging with it as an outsider is stealing or weakening that culture, is worrying. Much of the discussions I see about cultural appropriation are really proxy fights about racism and classism in the larger society, that get taken down to this quixotic and parochial level of trying to police whether people can have dreadlocks or if it is ok for a white woman from Australia to rap like she’s a black lady from the Bronx. It’s trying to address the pain and injustice of centuries of racism by dictating who can or cannot have cornrows, which seems to imbue things like cornrows (or saris, or jade necklaces, or twerking) with way more significance and power than they actually have, and ignores how fluid and ever-changing culture is. Your categorization of American music as theft is an example. The borrowing of ideas and cultures and influences that led to the creation of country, the blues, jazz, rock n’ roll, hip-hop, r&B, etc. was a good thing. That the economics of it reflected the shitty racism of that time is a bad thing

KatG

September 21, 2016 @ 4:15 pm

They aren’t “dictating” who has cornrows and who hasn’t, because they don’t actually have any power to stop people from doing that. Calling them the police is a fake victim game — and indicates that the people claiming they are being policed instead of simply criticized by others with equal free speech know that they are doing something that warrants the criticism and contributes to the societal problems.

Critics are pointing out that if you decide as a white person to get cornrows, you’re being hypocritical and bigoted and contributing to black people getting actually policed and facing real consequences for having their hair in cornrows. They are pointing out that Azalea has chosen to ape black musicians and reap greater benefits from it than the black musicians, who are often criticized or overlooked for doing rap music, taking advantage of racism in the music industry. Which she has.

See, you are advocating that white people should be able to exploit and profit from borrowing other people’s culture all they want, while ensuring that those people will not be able to benefit from that same culture and get punished for it in real time, and that the white people never receive any criticism or backflack from the people whose culture they willingly chose to exploit, shutting their critics up.

And they aren’t going to do that because if they don’t bring the issue up, it’s not going to change. It’s not a proxy fight — it’s the actual fight. It’s all part of the same thing — repressing non-white people while using what they create to make white people wealthier with the exact same things. White people who get cornrows don’t want to be criticized first because they aren’t used to it since they’re protected, and second because they know that it’s a crappy thing to do when black women are getting fired from jobs for having cornrows. So they actively want to repress black people from criticizing them. Free speech for them and not for the people whose creations they’re using.

As we all know, white people are not used to other racial and ethnic groups being equal to them in society and so many don’t see why they should be able to criticize white people freely. There were and are brutal mechanisms in place to stop that criticism. But a lot of brave people are standing up to those mechanisms and white people like Shriver are basically advocating for stronger mechanisms to shut those people down. She’s talking about violence towards non-whites — because that’s what happens when non-whites criticize white people in western societies — violence or the threat of it.

Artists are free to create what they want — and steal what they want. But they’ve never been free from criticism and cultural commentary from the public. But Shriver is trying to claim that she should be if it’s coming from the non-white people, that she should never have to hear that others feel she’s contributing harm to people or ripping them off to her benefit. And that’s what systemic bigotry is all about.

There’s a difference between cultural sharing (exchange without repression) and cultural exploitation used to further repress those cultures (colonialism.) Our racist society chooses the latter much more than the former. And that’s going to be criticized.

So you can think it’s wrong, or you can stop trying to pretend that music, fiction and other cultural expressions have nothing to do with our actual culture that is discriminatory, repressive and exploitive, that it is somehow separate and protected from criticism. Because if Azalea wants to ride the train of being just like a black rapper complete with accent but better because she’s a blonde white girl, then she’s going to get criticized for choosing that dynamic. Black artists are going to speak up about the inequality. That doesn’t stop her from having a music career — she gets a better shot at a career because she’s white. But it might start making her and her studio think about making fewer choices that are exploitive in her career. And it might give black artists a better shot in the industry and reduce the cultural idea that black rappers are bad and inferior to white rappers. Criticism can be part of the artistic process too.

Writing The Other (#SFWApro) | Fraser Sherman's Blog

September 22, 2016 @ 6:32 am

[…] we won’t be able to write anything good. Responding with intense disagreement, we have Jim Hines, Foz Meadows and the Venus Moon […]

Jan jansen

September 24, 2016 @ 6:54 am

Aha, so by dressing up as a minority i help getting this minority shot more often by the police. Right.

Care to explain your logic or provide at least evidence?

jan jansen

September 24, 2016 @ 7:23 am

Sally and KatG

I can write a book about blacks on leashes with two intends:

1. to show the absurdity and inhumanity of slavery

2. as a guidebook for my fourth reich.

Are you sure you want to judge both books the same?

(As a side note, notice how Jim Chines also uses the same superficial interpretation of Shriver’s story without even so much as acknowledging her explanation of the story).

(final note, you do not know my skin color, nor should it matter)

Sabrina Vourvoulias

September 24, 2016 @ 12:50 pm

Gross stereotyping and caricature has always had impact, including real violence. I suggest you start with the grotesque history of newspaper caricatures of Blacks, Mexicans, Chinese and Jewish folks, etc., and move forward from there. Nobody owes you research, Jan, or even a civil answer to the belligerence evinced in your comment.

jan jansen

September 24, 2016 @ 1:02 pm

You are right: Nobody owes me an explanation of their reasoning, you are right. In fact, it is their own responsibility to get their argument across and make it stand rebuttals.

Racist kills and racist portrayal are a consequence of racist thinking, not the other way around. Racist thinking is eradicated by ridiculing it and by showing its own hypocracy. Not by smearing people who might actually be allies in your quest for anti-racism and may have said, written or done something that you deem inappropriate based on superficial interpretation. What still counts as I show above is the intend.

At least Shriver had some good (self-deprecating) humor in her speech. You are a bunch of party-poopers who insist that where a sombrero is an act of disadvantaging Mexicans whatever the intend.

Fraser

September 24, 2016 @ 1:29 pm

“Racist kills and racist portrayal are a consequence of racist thinking, not the other way around. ”

It’s both ways around. Racist portrayals can confirm whatever stereotypes they were based on.

Whatever the original level of American racism was (I’ve heard different accounts and don’t know for sure), slavery reinforced and increased it. As several defenders of slavery argued at the time, black slavery gave whites a feeling of superiority, which gave them an incentive to be pro-slavery. And the rationale that because blacks were only fit to be slaves, not free, encouraged restrictions on free black Americans.

While racism did lead to the Japanese-American internment in WW II, it was fanned by whites for years (William Randolph Hearst actively promoted the idea of the Yellow Peril). And it doesn’t follow that because of existing hate for Japanese-Americans, the countless portrayals of them in WW II movies as stinking traitors (more than one movie assured us that the internment destroyed the Japanese espionage system in the US) couldn’t have made things worse.

The government certainly thought so. It pushed movie makers to portray Germany as a good country that had been taken over by Nazi fanatics, for fear that German = Nazis would make the post-war years tougher (they did not extend the same courtesy to Japan).

That said, “Critics are pointing out that if you decide as a white person to get cornrows, you’re being hypocritical and bigoted and contributing to black people getting actually policed and facing real consequences for having their hair in cornrows” seems like a stretch. How exactly does it prove you’re bigoted, or a hypocrite, let alone contributing to violence against blacks?

KatG

September 25, 2016 @ 8:17 pm

I did explain it. I can’t help it if you couldn’t follow it because you’re pretending large swaths of discrimination don’t exist. Shriver’s argument is that POC can’t criticize her writing because it bugs her and she’s white. She’s also been pretty openly racist, particularly in her speeches. In the same SF novel she wrote, the U.S. has been overrun by Latinos thanks to “lax” immigration policies and has a Mexican president who is dictatorial and has a lisp — a racist stereotype that is not a send-up.

But Shriver can write what she wants — and POC can criticize her work and her speeches, including what they see as poorly done portrayals that support bigoted views of their identities. Shriver’s insistence that they should not be able to do that is part and parcel of white people insisting that POC are inferior and their criticisms are illegitimate. And in our culture of institutionalized racism, there is a physical threat with white people being angry at POC. You can pretend it’s not there all you want; doesn’t change that it is. We physically get to see it happen.

Mexican Americans, when they go to university, are told repeatedly by white people that they don’t deserve to be there. That they got into to school as an act of charity, that their being there harms white people, that they are not welcome, that they are odd and not the mainstream normal like white kids. And traditionally, white people wearing sombreros — and having racists portrayals of Mexicans wearing sombreros in film and art — has been a way to mock Mexicans as inferior and send the same message. So when a bunch of white college students dances around in sombreros, making fun of Mexicans by laughing at their culture as their entertainment, it sends the same message to Mexican and Latino American students there — we run the school, you are inferior, you don’t deserve to be here and you aren’t welcome, and we can mock you whenever we want and you should be quiet about it because we’re in charge. That has historically been the message and it is still the message. And it is also the message that Shriver embraced as one that POC should have to put up with because white people’s mocking fun can’t be spoiled by a little education apparently.

And it is also a message that then starts to be used to justify harassing and acts of violence against Latino Americans — on campus and elsewhere. It’s a message of power. And in case you hadn’t noticed, white people are still in power in all areas in western societies. We don’t have an equal society for POC, and we have wide social attitudes that we shouldn’t have an equal society. So yeah, they criticize symbolism, cultural use, poor presentations of them by white people, being shut out of leadership positions and opportunities by white people rigging the system, outright lies white people tell about them, and clucking by white people that POC should be more respectful, quiet and less angry to the white people.

I’m white, but I’m damn tired of a bunch of white people freaking out that POC aren’t as scared anymore to speak up about the crap and discrimination they run into all the time and to work for an equal seat first off, and the white people insisting that as long as they personally and individually don’t intend to be racist, institutionalized racism and discrimination in our western societies isn’t going on. That’s a ridiculous assertion, but it’s the hill that Shriver has chosen to perch herself on. And for that, she’s going to get criticized.

As for the blackmail threat that POC better be nice to their “allies,” or they’ll get hurt — that doesn’t make you an ally, does it? Even if you’re POC yourself. It’s just a threat. And white people can pretend all they want that they are not making that threat, but they are. And they often back it up with violent official force.

When POC criticize white people, they aren’t trying to destroy them. They are trying to make things better for POC. But white people still first have to figure out that they can actually be criticized about this, even though they are in power, and start be willing to listen instead of trying to shut POC down or dismissing everything they say as a “fad.” As if fighting for their lives and their kids was a fad.