Uniform in the Closet, by Myke Cole

I’m home from Fandom Fest (which was a lot of fun!), and will be heading up north for vacation tomorrow morning. So I’ve handed the blog over to a number of guest authors, starting with Myke Cole. Have a great week, and I’ll catch y’all when I get back!

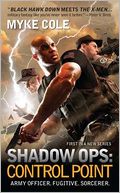

Myke Cole (Twitter, Facebook) is the author of Shadow Ops: Control Point [Amazon | B&N | Mysterious Galaxy], a military fantasy novel I reviewed here. He’s also the dungeon master who, with the help of Saladin Ahmed, made me fight goblins in our game at ConFusion earlier this year. He also got to be a fighting extra on The Dark Knight Rises, making him far cooler than I will ever be. This piece is an expansion of an essay he wrote for The Qwillery.

#

Uniform in the Closet: Why Military SF’s Popularity Worries Me

Myke Cole

We’ve got this problem, and I think it’s pretty serious. There’s a growing gap between those who serve in uniform and those who don’t. It’s the worst kind of gap: experiential, cultural. It’s the kind of gap that gives rise to rumor and suspicion. The kind of gap that endures.

In May of last year, the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, Admiral Mike Mullen, told the graduating class of West Point cadets that he was concerned about the growing gap between civilians and the military. In the United States, around 70% of youth are ineligible for military service due to health problems, criminal records, or other reasons. Of the remaining 30%, 99% elect not to serve. Currently, less than 1% of Americans serve in uniform. In a sour economy, recruitment soars, with a corresponding bump in educational and fitness standards, especially among the leadership. This makes the military, as it becomes more separate, more elite.

MSNBC’s Rachael Maddow addresses this question in her recent book, Drift. The New York Times’ Scott Shane summarizes her perspective:

“Only a tiny fraction of the American population serves or sends a family member to war, permitting a majority to remain oblivious to its grisly human price. . . . Contractors supply the battlefield support that once was the work of soldiers. A bloated security industry profits from the near-permanent state of conflict, sharing proceeds with pliable members of Congress. And now robotic drones carry out combat from an antiseptic distance.”

This is a serious problem, because America’s military is a citizen military. Our service members serve under the authority of civilians who are supposed to ultimately dictate policy derived from the vox populi of the American people. When the military fights, it does it for the royal you. That’s not the case in many countries. Look at Egypt or Burma, Guinea-Bissau or North Korea.

This is what has both Mullen and Maddow concerned. We don’t want to live in a country like that.

More importantly (as Maddow points out), having a military deeply integrated with the civilian population reminds everyone of the price of going to war, making it far more likely that we will do so only as a last resort. The bigger that experiential/cultural gap, the more likely Americans will simply shrug and accept that it’s time to lay down some ordnance. When the vast majority don’t have to buy war bonds, accept rationing, or offer up a family member, it’s an abstract, distant thing. A news item.

So, yeah. A problem. The genesis of the problem is a topic of much discussion in both civilian and military circles. The answer is complex, and like all cultural issues, will take a long time to resolve, but I am discouraged to see that the military’s own culture isn’t being examined in addressing it.

Let me get at it this way: We see members of the National Guard in their battle-rattle guarding train stations and airports. They are hidden behind tac-vests and magazines, Oakley Flak-Jacket sunglasses hiding their eyes. They look busy, alert. And they should. They’re guarding against threats. But when was the last time you saw a member of the military out to dinner, or the theater, or some public event in their dress uniform? Without a weapon? Not on Veteran’s Day or Memorial Day? Showing their service pride right alongside you?

There’s a great scene in a recent episode of Mad Men where Greg Harris (played by Samuel Page) has dinner out with his family. He sits in a crowded restaurant in his “Alphas,” (his service dress uniform) and tensely fights with his mother about his imminent return to Vietnam. It’s just a TV show, to be sure. But it’s one case where folks got the zeitgeist right. My parents regale me with stories of how service members used to wear their uniforms on every occasion that normally required a suit: Going out to the theatre, a fancy dinner, a formal party. Old movies feature plenty of scenes of servicemen donning dress uniforms to hop on a bus or plane.

You might still see that in Arlington, Virginia or Washington, DC. But what about in New York City? Or Billings, Montana? Or New Orleans? People never hesitate to thank me for my service once they find out that I have served. It’s inevitably followed by a slew of questions, interest and compassion. But finding it out in the first place is getting harder and harder.

And here’s where military culture comes in: There is a climate evolving that seeks to hide military membership. It’s largely driven by two concepts, both pushed to the forefront by the 9/11 attacks; “OPSEC” and “Force Protection.” It would put you to sleep to try and define them fully here (and hey, you’ve got Google and Wikipedia), but suffice to say that OPSEC culture attempts to protect sensitive military information (troop movements, ship and air schedules, etc . . .) and Force Protection tries to protect service members from terrorist attack (think, the USS Cole bombing). Both are genuinely important, both are needed.

Unfortunately, both are engorged by the panicked post 9/11 morass, the Clausewitzian fog of war that has us seeing terrorists and spies in every shadow. Both OPSEC and Force Protection seek, first and foremost, to protect the military by hiding it. Keeping a low profile is central to both cultures. OPSEC is centered around the concept that, if you are identified as a military member, you will be immediately targeted by those seeking sensitive information (state based spies, criminals, anti-government activists), smooth-talked, elicited from, eavesdropped on, blackmailed. Force Protection posits that a person in uniform will be grappled by a suicide bomber, knifed in a dark alley, pulled into a waiting van with blacked out windows. OPSEC forgets that sometimes the attractive foreign woman is chatting you up at a bar because she genuinely finds you attractive and is curious about you. Force Protection forgets that sometimes people take pictures of bridges and trains because they find them aesthetically beautiful.

And of course, like everything else in the military, contractors swoop in. Jobs are created. Training programs. Force Protection and OPSEC literature, PowerPoint presentations, degrees, classes, departments. Bureaucratic entities that, once created, will fight to sustain themselves at all costs.

Remember the “Loose Lips Sink Ships” campaign form World War II? An October 2010 Straight Dope piece put paid to that notion. Turns out that loose lips didn’t actually sink any ships. This in the middle of a major, existential struggle against an implacable enemy dedicated to our destruction. Yet the culture remains.

So, we have a hidden military. Wearing uniforms is discouraged off post. Showing one’s military ID is believed to invite either creeping spies or bloodthirsty terrorists. Force Protection and OPSEC moves the military into the shadows. Service members work, live and play alongside their civilian counterparts, and many of them don’t even know.

Those not in the military might be able to pick a service member out by a t-shirt slogan or bumper-sticker (I have been warned off both, by the way, in Force Protection and OPSEC briefings). But they mostly see and hear about military members in fictional accounts, news stories about PTSD related suicides, homicides. YouTube videos showing snapshots of firefights. Sensationalized accounts form tabloids. Wikileaks.

And, not surprisingly, stereotypes begin to evolve and blossom.

All stereotypes work this way: Without familiarity, whisper and rumor replace reality. Fighting men and women become the stuff of legends. It works the same way all stereotypes do: singular, easily recognized characteristics get taken, blown out of proportion, used to define an entire class of people. I knew this had reached epic proportions when the Shit my Dad Says meme finally reached us and the YouTube video Shit People Say to Veterans went viral. It was poking fun, to be sure, but we’ve all felt that wonder at the cluelessness of a public who seems not to know us at all.

But the real danger lies at the crossroads of exoticization and ignorance: The fetishization of a group of people. For one thing, discrimination (both positive and negative) against people is always presaged by this. If you don’t believe me, go check out the wild distortions currently used as the justification for the relentless persecution of homosexuals in Uganda. But in the case of our military, it has more ominous implications. We have become the newest minority, with all the ignorant and dangerous stereotypes that status affords.

So what does all this have to do with military science fiction?

Military science fiction and fantasy, as a sub genre, is a mainstay. From Heinlein to Weber to Ringo to Haldeman to newcomers like T.C. McCarthy, genre books dealing with the military fly off the shelves. Heck, publishers like Baen practically stake their whole business on it. A lot of the newer, edgier fantasy hitting the market these days has a military cast to it (Joe Abercrombie’s work deals largely with medieval warbands, the military of their time. George R. R. Martin’s A Song of Ice and Fire is a decidedly military epic in many respects). That’s not even counting the movies. Battle: LA, Lockout, Battleship, Act of Valor. Dynamite Comics recently released short digital novels by Chuck Dixon (of Batman fame). The topic? SEAL Team Six. The last time I checked, the first volume was #643 (out of over 700,00) in the Kindle store and #24 in the Action and Adventure category.

And I started thinking about why. Military stories have always been popular, but why are people buying them now? What is it about today’s military service that folks find so fascinating? The answer is deeply troubling. This is the culture gap in action. People are fascinated with the modern military precisely because they are disconnected from it. Like people flocking to the zoo to see the rare Siberian Tiger, they are drawn to military speculative fiction by the sense of wonder that comes from experiencing the rare, the different, the exotic.

And in this case, that’s a serious problem.

Familiarity and kinship with a military is critical to ensuring it remains a servant of civilian masters and their policy. All military members must remember that, they too, are civilians. When they get home from work and take off their uniforms, they shop and play and raise their kids in the midst of everyone else. Distance breeds fantasy and mistrust. A military punctuated by the uneasy humor of that YouTube video. A civilian population unsure of what a man or woman in uniform, suffering from PTSD, might do to them if they get too close.

The healthiest relationship between a military and civilian populace is one of tight integration. The message I’d like to see repeated is “We are you, and you are us.” It is the best way to ensure that the military remains an instrument of civilian policy, and never a force for setting it.

It’s my sincere hope that interest in military science fiction (and fantasy) will move beyond a fascination with the other. The real military is a cross-section of all of American society. We have mavericks and hidebound rules-lawyers. We have lockstep loyalists and anti-authoritarians. We have heterosexuals and homosexuals. We have artists, dreamers and intellectuals. If you see it out there, it’s in here. We are you, and you are us. That depth and complexity of character makes for the best writing in any genre. Here’s hoping we’ll see more of it in military speculative fiction, and that the sub-genre can be used as a tool to bridge the gap that Mullen and Maddow have described.

Thoraiya

July 2, 2012 @ 11:53 am

Great essay!

But I think you’ll always find someone to exoticise if you try hard, because not every community can be a microcosm of the world.

There’s an infantry base near our town, and I love it that my 3-year old can be at the supermarket and see a bunch of guys in camo arguing about which kind of bacon is the best or how much coffee they still have at home. She loves shouting out, “look Mummy, boy soldiers!” (Or “girl soldiers!” as the case may be. Kids are the gender police, that’s for sure).

It’s a very white town we live in, though. She’s seen, what, one or two black guys in her whole life? (“Look, Mummy, it’s Gordon from Sesame Street!”) There’s no Asians here, either, or Islanders, and because the only guy with a turban is the one pushing trolleys around in the car park, I am a teensy bit afraid that she’ll grow up thinking all people with turbans push trolleys, instead of understanding that turban-people “have mavericks and hidebound rules-lawyers. We have lockstep loyalists and anti-authoritarians. We have heterosexuals and homosexuals. We have artists, dreamers and intellectuals. If you see it out there, it’s in here. We are you, and you are us.”

You just keep writing Military SF about soldiers that are real people, and we’ll keep reading. And my kid will keep spotting soldiers playing cricket, soldiers doing wine-tasting in fine dining establishments, soldiers smashing beer bottles in parks and soldiers picking up roadside garbage on their own time, and she’ll get that you aren’t aliens from another planet long before she’s old enough to pick over my SF bookshelves, I hope 🙂

Paul (@princejvstin)

July 2, 2012 @ 12:52 pm

People are fascinated with the modern military precisely because they are disconnected from it.

Yeah, I think this is the centerpiece of your thesis, Myke. People are often fascinated with things they have no connection to. It gets airbrushed, glamourized, rubbernecked. The dirt, grime and danger of the military is obscured by the spit and polish seen on TV.

neth

July 2, 2012 @ 2:07 pm

Very interesting article. And from my limited perspective as a citizen with relatively little connection to the modern military (though I have brother in law who’s a lt. colonel in the Army), I think this is pretty spot-on. When I read your book, the military aspects, all the acronyms and culture was as much fantasy as the magic and elves.

Matt

July 2, 2012 @ 2:09 pm

I admit that I find the Swiss model far more appealing, having a large professional military so isolated from the civilian population can lead to problems, including “we’re paying for these guys, let’s use them for something” without thinking the soldiers are human beings and may pay all too great a price.

I’ve read a lot of military SF and it has given me a much deeper understanding of the horrors of war and a greater motivation to avoid it if at all practical. War is a very bad thing, but sometimes all the other choices are worse.

Eric C.

July 2, 2012 @ 3:17 pm

Myke,

Looking ahead, let’s assume that the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq wind down, but the “shadow wars” continue (please let me know if you don’t agree with this assumption and why). Do you think this disconnect is likely to get worse, especially as war becomes the province of special forces and drones, operating with little scrutiny from the American public.

Second, think of the drone operators that wake up in the US, see their kids off to school, then go to war for an 8-hour shift, leaving in time to see Timmy’s t-ball game (as explained more in books like WIRED FOR WAR). Do you think a secondary disconnect might develop inside the minds of the military, either among the drone operators themselves or the larger military itself (assuming drones keep taking a bigger role)?

Thanks for the essay. Can’t wait for Fortress Frontier.

Liz

July 2, 2012 @ 6:18 pm

I lived in Greece for a year and 4 months back in 1982-84. All young men were drafted for 2 years at 18 -no deferments for anybody. They were trained and worked at many tasks when they were needed. What I found interesting was that they were ubiquitous – you saw them everywhere in uniform. Much of the time they were on leave, I suppose, since they were eating in restaurants, drinking in cafeneion, etc. But they also were there on duty. When I lived in Nauplion, at Easter, they were part of the Good Friday procession that went through the town, carrying Jesus’s coffin (that’s part of a very intense Holy Week celebration you see in Greek villages). They were in military mourning – and dispersed through the crowd with the locals. I don’t know if you can still see this in Greece – it’s been 30 years. But it was taken for granted by Greeks that the military was there, and that it was part of the community. I haven’t thought about this for years – your essay brings it back. Thanks.

How Would You Like To Be A Part Of The Supernatural Ops Core? | Ferrett Steinmetz

July 6, 2012 @ 11:03 am

[…] […]

Peter Eng

July 6, 2012 @ 11:57 am

“But I can’t shake the unease that my readers are drawn at least in part from a fascination with a culture that seems exotic because it has been made distant by the measures put in place to protect its members.”

That may be part of it for me. But the part that my subconscious isn’t burying where I can’t find it says that I’m reading military SF because it’s a well-written science fiction, not because it’s exotic. Well, that and because there’s a part of me that hates the idea of sending anybody out to fight, volunteer or draftee, because it virtually guarantees that somebody’s going to come back on a stretcher or in a coffin. If I have the choice, I’d rather reinforce my opinion by reading a novel rather than reading it in the paper.

Brenn

July 6, 2012 @ 6:22 pm

My family has a strong service record. I have cousins in every branch of the service at the moment, actually. I read Mil Sci-fi because it keeps me on familiar footing with them, helps me understand them a bit better since I opted out of going Marines (part of me wishes I had, ahh regrets). I also work with a lot of guys who have served. So on their behalf, I say keep writing. As that gap keeps widening, we need stories to educate that yeah, soldiers are just human beings too.

This post also highlighted a bit of my ordinary world that I’ve been taking for granted. I won’t any more.

Kathryn Scannell

July 8, 2012 @ 12:00 pm

I think you have a very real point about the disconnect. The fascination is not limited to just readers of SF either. If you wander over to the romance shelves (don’t worry – you scrub off afterwards), it seems as about half the alpha heroes are military men, and always the elites – Navy SEALS, Army rangers, etc. Unfortunately far too many of these books aren’t well researched, and for many readers they’re the only exposure they have to the military.

I don’t have a huge exposure myself – just research and spending a lot of social time with ex-military friends (mostly grunts and non-coms) – but enough of their attitudes have gotten across to me that I read these books and cringe at how wrong the portrayals are. I suppose realistically portrayed military wouldn’t sell as well in a romance as the nice shiny, super-soldiers, but it still bothers me.

I don’t know but I’ve been told « Play It All Night Long

July 9, 2012 @ 3:50 pm

[…] And I started thinking about why. Military stories have always been popular, but why are people buyi… […]

Susan

July 9, 2012 @ 10:17 pm

Thanks for the thought-provoking post. I have your book in my Kindle TBR pile, so I guess I need to move it up to the top now!

My family has a long history of military service and I’m lucky to have a rich visual record of this (going back to Civil War tin-types and letters). But, for perhaps the first time, there’s no one in the current generations in the military. It’s sad to see the end of the tradition, but we still have an affinity for military and public service.

My father was career military and we lived on military bases all over the US and the world. I was accustomed to seeing dad in his uniform on a daily basis. Unfortunately, there were some postings where service members were specifically requested not to wear their uniforms in public/to work because of hostility/danger from the local population. This wasn’t just overseas; it also happened for several Pentagon postings. It was sad to see my father head out to work in a suit for the first time, as if he were in some kind of shameful disguise. I doubt this continues today (at least for US postings), but it’s a demonstration of the post-WWII us vs. them divide between civilian and military that has just continued to grow. Maybe books like yours can help narrow the gap.

силиконовые браслеты купить

September 4, 2012 @ 3:59 am

Hello, i believe that i thought you visited my website that is why i came to go back the suggest?.I’m attempting to find things to progress my website!I guess its ok to use some of your theories!!